When Mr. Joel Swanson steps into the broadcast booth, it’s as if he’s entering his own laboratory—a place where the unpredictable elements of live sports mix and react.

Over the airwaves, the veteran science teacher’s voice becomes the nucleus around which the game orbits, holding together the action, the drama and the story unfolding on the court or the field.

With the headset on, Community’s biology teacher dissects the action, revealing the inner workings of Illinois Wesleyan football, of Lexington High School basketball…

On the radio, he’s a Dr. Frankenstein of sorts, bringing life to each contest he calls.

Swanson’s over two decades in the press box didn’t just happen by chance. His love of sports is in his DNA, a trait inherited from his father.

“My dad was a high school basketball coach for 51 years,” Swanson said.

In fact, at 78, Paul Swanson is still coaching as an assistant on the Calvary Christian Academy basketball team’s staff.

His dad’s coaching career, helming high school basketball and football teams around Central Wisconsin, meant a love of sports was “ingrained” in the younger Swanson “from the very beginning.”

It just multiplied and expanded over time.

And when it comes to athletics, Swanson only has one true love.

“I grew up with basketball,” Swanson said. “That was my world.”

But when Swanson graduated high school–after two-season’s running the point for the River Valley Black Hawks, his dad as his head coach–his playing career was over.

To say basketball “was” Joel Swanson’s world is a lie. The past tense is inaccurate–it still is. Basketball, in all its forms–the professional to college to high school hoops–remains Swanson’s favorite sport.

Just how deep does his love go? An anecdote: Swanson, a Wisconsin native, might be the only person to own two copies of “100 Years of Madness: The Illinois High School Association Boys’ Basketball Tournament,” a commemorative history of Illinois high school hoops.

Those early years watching alongside his father, playing for him, built a passion for the game that would later mutate into a love for sports commentary.

Swanson’s broadcasting career, he said, has been primarily at the high school level and calling Illinois Wesleyan sports.

The catalyst that started it all came in 1995, partnering up with his dad to call high school playoff basketball.

“I was the play-by-play guy; he was the color commentator,” Swanson said, covering Dodgeville’s contest against Cuba City.

“They eventually made it to state,” Swanson said, “so we ended up doing a couple of games.”

Those were tape-delay broadcasts back when broadcasting high school sports “was just getting started.”

Expectations were low and the experience, Swanson said, was “really fun, “especially” doing it alongside his dad.

It would be a few years before Swanson was back on the “air,” calling local high school competitions during his first year at the University of Wisconsin-Richland.

Swanson’s equipment? “Basically a tape recorder.”

“There was nothing called live streaming. That didn’t exist.”

“You would tape the game and then the local cable company would put it out [sometime later] during the week.”

Sometimes, they’d run that game “seven, eight times” over the week, Swanson said.

“That’s kind of what got me started.”

As he tells it, Swanson’s journey into broadcasting evolved naturally, almost by chance.

As a college student working at WRCO in the late 1990s, a radio station in Richland Center, Wisconsin, opportunities seemed to find Swanson.

“Somebody says, ‘Hey, we need a fill-in,’ and I do it,” he said.

What started as a few games here and there quickly snowballed.

“They’d ask, ‘Why don’t you do a couple more?’” Swanson recalled.

And just like that, one game led to another, and his broadcasting career began to take shape, built on the simple willingness to say yes and step in whenever needed.

“That’s kind of generally how I’ve gotten into most of the broadcasting positions I’ve had,” he said.

And for someone who started off by filling-in, someone moonlighting in the booth–he’s been pretty prolific.

Last Friday, with Ironmen football on the road, so was Swanson. The broadcaster was in Tremont covering the El-Paso Gridley High School Titans football contest for Route 24 Radio.

Saturday at 1 p.m., Swanson donned the headset at IWU’s Tucci Stadium, calling a collegiate Titans contest as Wesleyan took on Millikin University’s Big Blue.

This Friday, Swanson goes live from Dick Tharp Field for the Inkspot as the Ironmen look to win an outright Big 12 Championship.

It’s safe to say Swanson has found his calling calling games.

But he is still a scientist at heart.

Swanson approaches each game with scientific precision; he pours over film over data. He breaks each team, each player down to its basic elements.

He’s looking for patterns, for trends; he’s putting everything under the microscope.

That research, Swanson says, is essential to his success on air.

“You’re able to better anticipate things that are going to happen,” he says. “In basketball, a certain team goes into a certain defense, and I know how to break this defense down.”

His approach, mirroring the precision of an experiment, puts him in the position to analyze the action in real time—he gathers data, observes patterns–and draws conclusions.

And while Swanson’s calls serve as the broadcast’s nucleus, it’s the surrounding elements—the players, the score, the crowd’s energy—that create the reaction that keeps listeners engaged.

When he’s on the air, his goal is clear: to paint a picture for his audience, whether they are watching or listening.

On the radio, his descriptions are magnified, zooming in to an almost cellular level, ensuring that listeners can visualize the game without seeing it.

“You’re painting a picture because they can’t see,” Swanson says. “You have to describe the atmosphere, who’s doing what, so they can visualize what’s going on.”

When he’s live streaming, his role shifts to offering context and analysis, focusing on the critical moments that define the game. What they mean and why they matter.

As a broadcaster, Swanson’s role is often twofold: play-by-play commentator and color analyst.

“It’s actually fairly rare for somebody to do both,” Swanson says. But “when you’re doing small-time broadcasting, you’re going to do whatever is asked of you.”

That’s Darwinism, in a sense, survival of the fittest, adapting and surviving.

Adaptation is critical during a live broadcast, as no two games are ever the same—each brings a unique combination of variables that Swanson must navigate. Hours-long lightning delays, blowouts where the outcome has been long decided and game-winning buzzer-beaters are all part of the ecosystem of sports broadcasting.

Swanson’s approach to each game is shaped in the moment, by the moment, the atmosphere and the unpredictable twists that sports inevitably bring.

“You have to prepare yourself for any situation that could pop up,” Swanson said. “It’s not like a movie. There’s no script.”

“There have been times where I have really prepped hard for broadcasts,” Swanson said, “because I’m like, ‘Okay, this is going to be a blowout. And I’m going to need something to talk about.’ And then it ends up being a one or two-point game. I’ve had some other times I thought, ‘this is going to be a really close game,’ and it’s been a blowout.”

“You just never know how a game is going to go. I mean, games just go so many different directions.”

For Swanson, that is where the thrill lies, in this unpredictability—the possibility that any game could shift dramatically, requiring him to recalibrate his approach on the fly.

That thrill is Swanson’s real payment for the hours and hours of work he puts in.

“I don’t make a tremendous amount of money doing it,” Swanson said. “I just do it because I enjoy it.”

That internal reward is a good thing for Ironmen fans, as Swanson’s work covering Community football and basketball is pro bono.

It’s Swanson’s emotional and intellectual fulfillment that keeps him coming back to the booth.

And sometimes a little bit of a rooting interest.

“I try to be as objective as possible,” Swanson said. “I try to be fair but I always will have a slight rooting interest for Normal Community or for Illinois Wesleyan.”

While that interest in the Ironmen is inherent, Swanson’s love for Illinois Wesleyan evolved overtime.

“I did not really have any connection to the school before I started broadcasting,” he said, “but I have become a big fan just because the programs are so good. [The] people are so good.”

“When you build relationships with the people in the program, it is very easy to cheer,” Swanson said.

The Ironmen and the Titans, “the kids and the coaches,” Swanson said, “are very easy to cheer for.”

Swanson makes building relationships look easy.

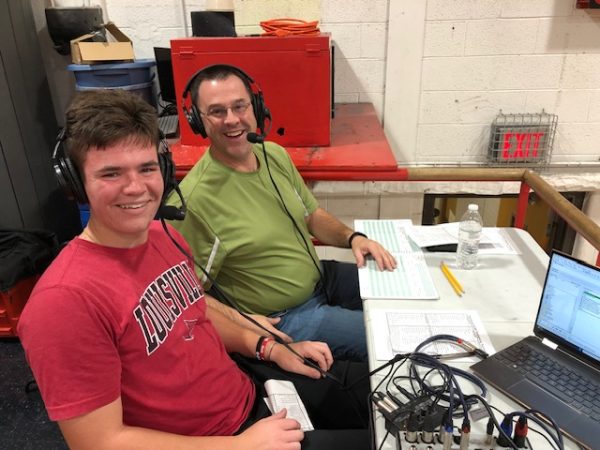

Whoever his partner in the booth–Ben Webster, an El Paso High Schooler on Route 24 radio; Eric Stock, someone Swanson’s worked with since 2005, covering IWU; or Community senior Zachary Knox-Doyle–chemistry is never lacking.

(Mr. Brad Bovenkerk)

Listen long enough and certain elements of Swanson’s personality become crystalline–he’s humble and generous, considerate and collaborative, he’s magnanimous.

Before a broadcast begins, he visits with opposing coaches, checking the pronunciation of athletes’ names; he closes contests recognizing the contributions of every crew member; he looks for opportunities to engage his broadcast partner and share the air.

And despite being a little bit of a homer, Swanson’s calls are always fair; always congratulatory.

“At the end of a game, if whoever I’m broadcasting for has lost, [I’m] trying to give the other team credit for what they have done.”

He gives credit where credit is due.

And if the team he’s calling wins, Swanson looks to celebrate the successes of the loser, pointing out “the good things they did in this particular game,” regardless of the final score.

He finds wins in the losses.

“I’m always very conscious about that,” the broadcaster said.

It’s come full circle for Swanson. He is no longer the young high schooler learning the ropes alongside the seasoned sports veteran. Now, Swanson is helping launch the careers of the next generation of sports commentators, mentoring the Inkspot’s journalists as they venture into live broadcasts.

“I probably enjoy doing the Inkspot broadcast as much as anything that I’ve done,” Swanson said, watching young journalists develop, getting more comfortable, getting better, becoming their own person on the air as the livestream over YouTube.

Helping students hone the craft, their commentary skills, Swanson said, “is probably more rewarding than anything I’ve done.”

And it is still in the DNA.

When he wasn’t calling Community basketball games last season, Swanson and his son Tyler were courtside in Lexington, the elder Swanson still doing play-by-play, Tyler with the color commentary.

Photo Courtesy of: Route 24 Radio // Route24radio.com

On the drive to the game, Joel Swanson asked his son if he’d be interested in “hopping on” the air for a little bit, a quarter or so.

Tyler ended up calling seven or eight games with his dad by the season’s end.

Head to YouTube, and you can find a young Joel Swanson and his father Paul calling their first basketball game together in the mid-’90s, preserved like an old sample on a microscope slide.

Now, digitally fossilized are the first calls of the next generation of broadcasters – the Ben Websters, the Zach Knox-Doyles, the Tyler Swansons, perhaps, with Joel Swanson, a seasoned voice in Bloomington-Normal’s sports ecosystem alongside.

It all comes full circle.

![Community honors longtime coach Mr. Bryan Thomas before Oct. 3 game [photo gallery]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Thomas-6-1200x1200.jpg)

![Playoffs Rd. 1: Coach Drengwitz on Ironmen’s 7A playoff opener at Carmel Catholic [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/PW_PresserVCC_Thumb.png)

![Halloween candy cross section quiz [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Candy-cover-big-900x675.png)

![Average Jonah? [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/average-jonah-900x600.png)

![[Photo Illustration]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/trigger-words-1.png)

![Hauntcert performers on why this year’s show hits all the right notes [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Untitled-2.png)

![Ironmen volleball head coach Ms. Christine Konopasek recorded her 400th career victory Oct. 21 as the Ironmen closed their regular season with a 2-0 sweep over Danville.

[Photo Illustration]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Vball400Thumb.png)

![Week 9: Coach Drengwitz on Week 8’s win, previewing Peoria High [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/W9_PeoriaThumb.png)

![Postgame: Drengwitz on Community’s 56-6 win over Champaign Centennial; staying unbeaten in Big 12 [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/10.17_FBwChampCent56-6_POST_thumb.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Halloween [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/tot-Halloween-YT-1200x675.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Fall favorites [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/ots-fall-web-1200x800.png)

![On the Spot – Teachers tested on 2023’s hottest words [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/On-the-Spot-Teachers-tested-1200x675.png)