After a storm of backlash, Scholastic reversed its decision to allow school districts to omit books that deal with race, LGBTQ+, and other issues related to diversity from publisher’s book fairs.

The children’s book publisher, in an Oct. 13 press release, announced the decision to create a special collection of diverse titles, “Share Every Story, Celebrate Every Voice,” for elementary school book fairs.

The collection’s creation–with books on race and sexuality–was intended to allow elementary schools in states with literary bans to continue hosting book fairs without fearing legal repercussions.

Restricting the diverse titles to a special collection would allow Scholastic to continue offering “these important books,” the company said, allowing schools to decide what options were best for students based on their local laws and policies.

“We don’t pretend this solution is perfect,” the press release said, “but the other option would be to not offer these books at all–which is not something we’d consider.”

The 64 books in the collection included titles on historical figures like “I Am Ruby Bridges” and novels explaining sensitive topics like “Refugee.”

Critics, from free speech advocacy groups like Pen America and the American Library Association to Scholastic authors and educators, noted that creating a collection solely of diverse titles made it easier for schools to opt out of the diverse offerings–regardless of state laws and local policies.

Less than two weeks later, Scholastic released another statement backtracking: “We understand now that the separate nature of the collection has caused confusion and feelings of exclusion,” the statement said. “We are working across Scholastic to find a better way.”

Scholastic announced the collection would be removed come January, adding that they would continue to work in accordance with states’ restrictive laws while still condemning literary censorship as a whole.

“It is unsettling that the current divisive landscape in the U.S. is creating an environment that could deny any child access to books,” the Scholastic statement said.

Pen America, an organization promoting free speech and literacy, acknowledged, in criticism of the collection created, the difficulties facing librarians and educators.

But those dangers, the organization said in a statement, do not outweigh the “risks [of] depriving students and families of books that speak to them.”

One such risk, Dr. Roberta Trites, a children’s and adolescent literature scholar, said, is fostering intolerance.

“Lots of evidence from colleges of education and schools of psychology,” Trites, a retired Illinois State University English professor, said, “shows that people who are exposed to more diversity, become more tolerant.”

That tolerance is rooted, Trites said, in children’s literature’s ability to cultivate empathy.

“When you read a story about someone living with these differences,” Trites said, “you grow in your empathy. It increases your power to imagine how the other person feels.”

As young girls, both Trites and Community’s Instructional Media Center specialist, Mrs. Caroline Fox Anvick, read books that expanded their worldview.

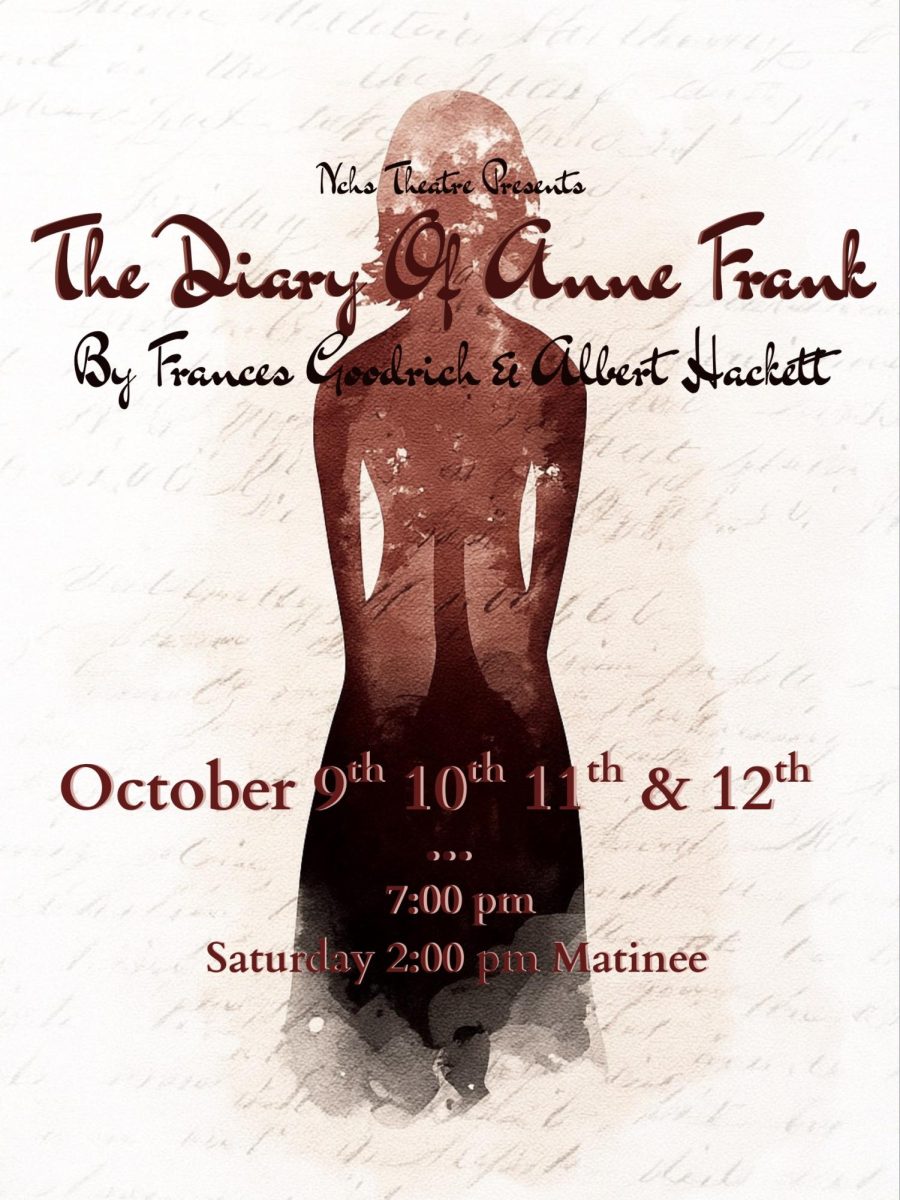

“I read ‘The Diary of Anne Frank,’” Trites said, “because so many of my classmates were going through bar mitzvahs and bat mitzvahs.”

“Did I know what it was like to be Jewish and living in fear for my life? No,” Trites continued, “but I gained a lot of empathy.”

Fox Anvick had a similar experience as a young reader growing up in a small town.

“When I was little there was a series of books called the ‘All Of A Kind Family.’ It was a series about a Jewish family,” Fox Anvick said.

“I knew nothing about Jewish people growing up.”

That was something her exposure to the book series changed.

“I wish every kid had that experience,” Fox Anvick said.

But censorship limits access to those diverse experiences by restricting access to information.

Access to information is something that Trites believes is a cornerstone of American education.

“A free country has to have free access to information,” Trites said. “That’s what libraries are all about. If we start censoring them, we start giving up freedom of speech.”

Illinois is aligned with these beliefs, becoming the first state to outlaw book bans this June.

Maintaining access to diverse titles in libraries, Fox Anvick said, creates “windows and mirrors.”

The librarian wants students to be able to look at a book cover and “see themselves” and “their experience.”

But books, Fox Anvick said, are also windows, offering a “glimpse into another world.”

Trites and Fox Anvick agree that parents should have a say in what windows and mirrors their children peer into. But a parents’ say should not extend beyond their children.

“Parents have a right to say what their own children should or should not be reading,” Trites said. “They have zero right to tell other people’s children what they should be reading.”

The censorship issues, Trites said, come in “cycles.”

The recent Scholastic controversy, Fox Anvick said, stems from the fact Scholastic is a business.

“They were just weighing which side was going to enable them to continue making money,” Fox Anvick said.

Although it took time, Fox Anvick said, she was glad they “went in the direction that they did.”

“We need more companies or corporations standing up to these types of laws because,” Fox Anvick said, “money talks.”

![Community honors longtime coach Mr. Bryan Thomas before Oct. 3 game [photo gallery]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Thomas-6-1200x1200.jpg)

![Ironmen volleball head coach Ms. Christine Konopasek recorded her 400th career victory Oct. 21 as the Ironmen closed their regular season with a 2-0 sweep over Danville.

[Photo Illustration]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Vball400Thumb.png)

![Halloween candy cross section quiz [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Candy-cover-big-900x675.png)

![Average Jonah? [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/average-jonah-900x600.png)

![[Photo Illustration]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/trigger-words-1.png)

![Week 9: Coach Drengwitz on Week 8’s win, previewing Peoria High [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/W9_PeoriaThumb.png)

![Postgame: Drengwitz on Community’s 56-6 win over Champaign Centennial; staying unbeaten in Big 12 [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/10.17_FBwChampCent56-6_POST_thumb.png)

![Week 7: Coach Drengwitz recaps the Ironmen’s win over Bloomington, talks Danville [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Vikings-feature-Image-1200x675.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Halloween [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/tot-Halloween-YT-1200x675.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Fall favorites [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/ots-fall-web-1200x800.png)

![On the Spot – Teachers tested on 2023’s hottest words [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/On-the-Spot-Teachers-tested-1200x675.png)