Distance Running Animals

How far can the human body go?

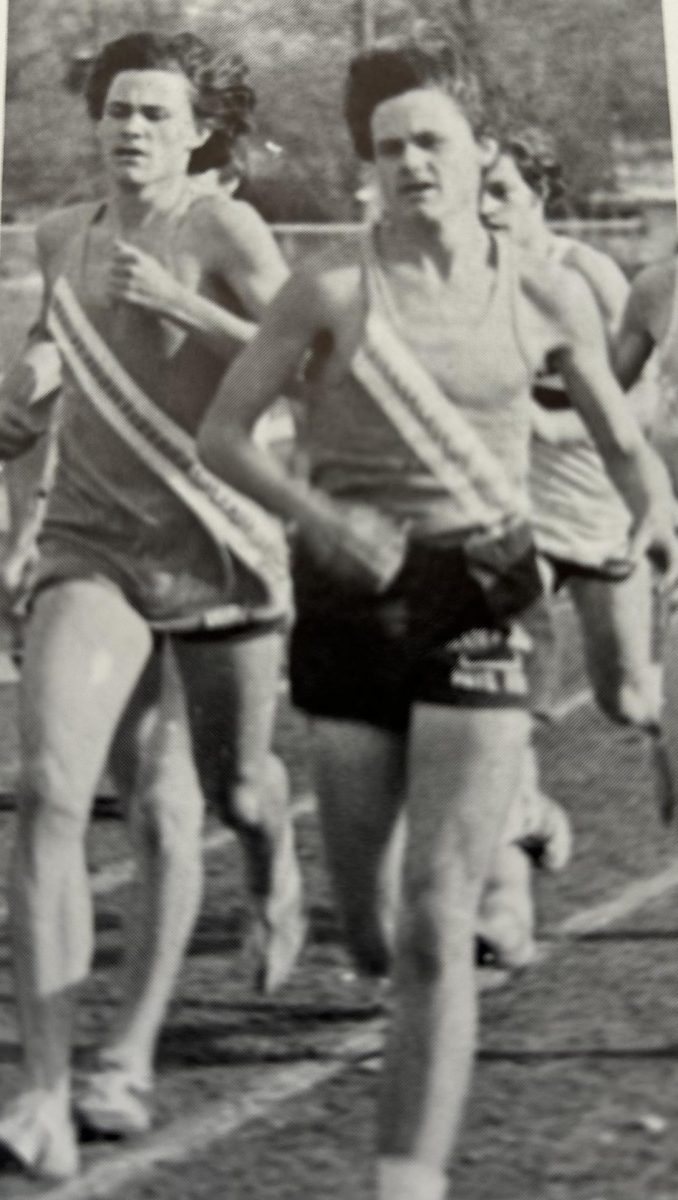

That was the question on the minds of three 20-year-olds when they laced up their shoes and took to the Glenbard West High School track.

A grueling 196 miles in 24 hours.

This was the world record the Patten twins, Tom and Den, along with their friend Larry Turilli, set their sights on—a Herculean feat that would test the very limits of their endurance and willpower.

The concept was simple: one runner would complete a mile, baton in hand, pass it off to the next runner, and repeat. The relentless relay would continue, with the baton in motion at all times. The trio had 24 hours—from 9 a.m. to 9 a.m.—to conquer as many miles as possible.

They crunched the numbers. To tally 197 miles in a single day and secure their place in running lore, the trio would need to run at a clip of 7:15 a mile.

14 minutes and 30 seconds of rest.

Then, they would do it again. And again. And again—each cycle pushing their bodies closer to the brink of exhaustion.

The early miles flew by in a blur of determination and speed. The Pattens and Turilli churned out sub-6:15 minute miles. They were on track to make history.

Morning melted into late afternoon, and afternoon gave way to evening. A storm swept in, and the June temperature plummeted into the forties. Yet, the trio continued to rack up the miles, undeterred by the chilling rain.

1 a.m.—156 miles down, eight hours to knock out the final 41.

After 16 hours, mile after mile, stride after stride, one mile of running, two miles of rest, the young men’s bodies felt the effects.

Just a few short hours before dawn, their dream began to slip away like the fading stars in the early morning sky.

Den Patten watched as his brother tightened up on one of his legs of the relay.

“Tom strained something in the back of his knee,” Den recounted. “He couldn’t keep running.”

But Den and Turilli willed on—their 12, 13 minutes of rest now cut to eight.

They willed on.

For about 10 more miles.

“We … tr[ied] for about five more miles each,” Den said, “and after another five miles, we just said, ‘okay, we’re not going to be able to do this.’”

167 agonizing miles in seventeen hours of running—29 miles shy of glory.

“It was a major frustration,” Den said, “because if Tom had not gotten hurt, we could have just easily reached that.”

Although they fell short of their ultimate goal, their achievement remains a testament to their dedication and the unyielding support they gave one another—a feat that would have never reached the starting line without their collective determination, without each other.

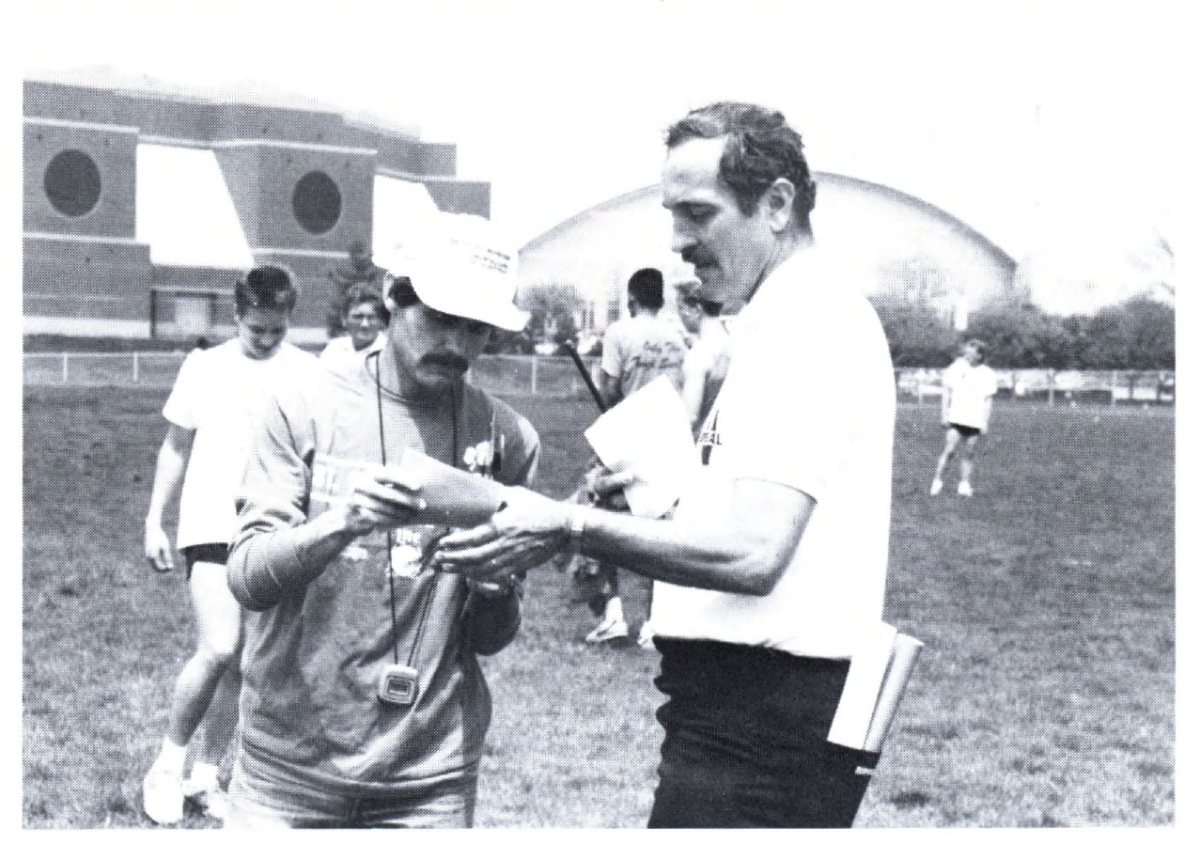

When Tom interviewed for an English teacher position at Normal Community High School, he mentioned being interested in coaching track, a passion rooted in his own running experiences.

Image Courtesy: Reverie Yearbook

It would take three years before Tom Patten would takeover as head coach of the Ironmen’s cross country program; when he took the role, the younger Patten invited his brother along.

“I would have never had that opportunity to get into coaching,” Den said, “if Tom had not been a high school teacher and been so gracious about letting me be part of the team.”

That sense of belonging, the intrinsic feeling of being part of a team, lies at the heart of the Patten brothers’ coaching philosophy.

This philosophy is the core of the “Distance Running Animals,” a moniker Community’s distance runners have worn for ages.

It’s a name that members of track and cross country teams boast proudly—a tradition that has thrived since the Patten brothers’ early coaching years.

A Distance Running Animal possesses “some kind of specialness,” Tom explained, a unique blend of grit and spirit that sets them apart.

What traits must one possess to be counted among this exceptional breed?

These kids stand out from the ordinary students walking the halls at Community, Tom said. They are relentless creatures, constantly striving to improve, to better themselves, mile after grueling mile, day after day.

In running, this is a challenging task to do day in and day out, mile upon mile.

“Running stresses the body, and you have to learn to deal with that … it’s also mentally hard,” Den said. “You have to be strong-willed to deal with what you know is going to be discomfort.”

But these animals aren’t lone predators; They are pack. A herd. A flock. Their true strength lies in their numbers, in the unity and camaraderie that bind them together.

“It’s the shared sense of realization that it’s hard to be a runner … that is one of the biggest reasons that runners are so supportive of each other even though they are competing because they know you’re working hard and you’re doing things no other people want to do,” Tom said. “It’s easy to be supportive of other people when you know what they’ve gone through because you’ve done it yourself.”

This mutual support among runners, epitomized by the twins’ own relationship, makes the sport bearable, even when the challenges reach their most daunting peaks.

“It’s invaluable having people around you, providing not just the physical support of someone next to you that you’re trying to hold on to or stay ahead of, but just that mental benefit of we are doing this together,” Tom said.

For Tom, that support came from Den. For Den, it was Tom.

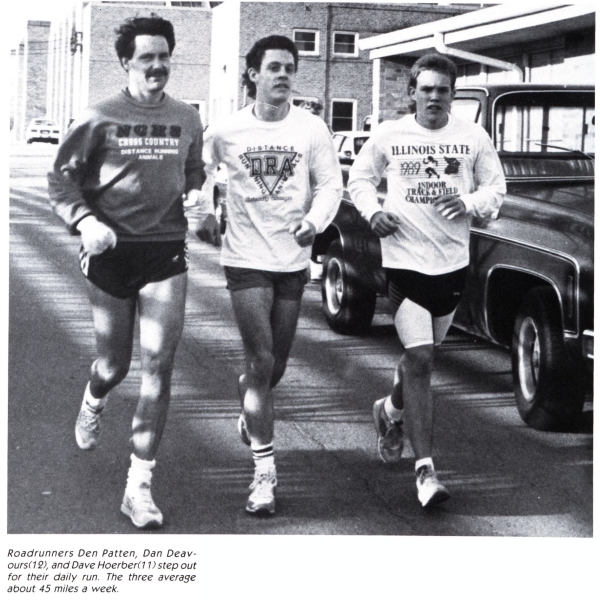

Image Courtesy: Reverie Yearbook

“We can be a sounding board with each other but then pick each other up when we’re feeling frustrated or disappointed,” Tom said.

After high school, Den would attend Illinois Benedictine College in Lisle while Tom enrolled at Chicago’s Loyola University where they both would continue running.

“We went to a Catholic High School, so they really pushed Catholic colleges,” Tom said. “We both really had very good freshman years in college and ran some really good races, but neither one of us liked the school we were going to.”

Was it the school they didn’t like or was it the separation from their other half?

“After one semester, we both left,” Tom said.

The next year the brothers enrolled together at Illinois State University, and have been almost inseperable ever since.

For years, the Patten twins leaned on each other.

Now, the distance runners at Community would benefit from the guidance of both twins.

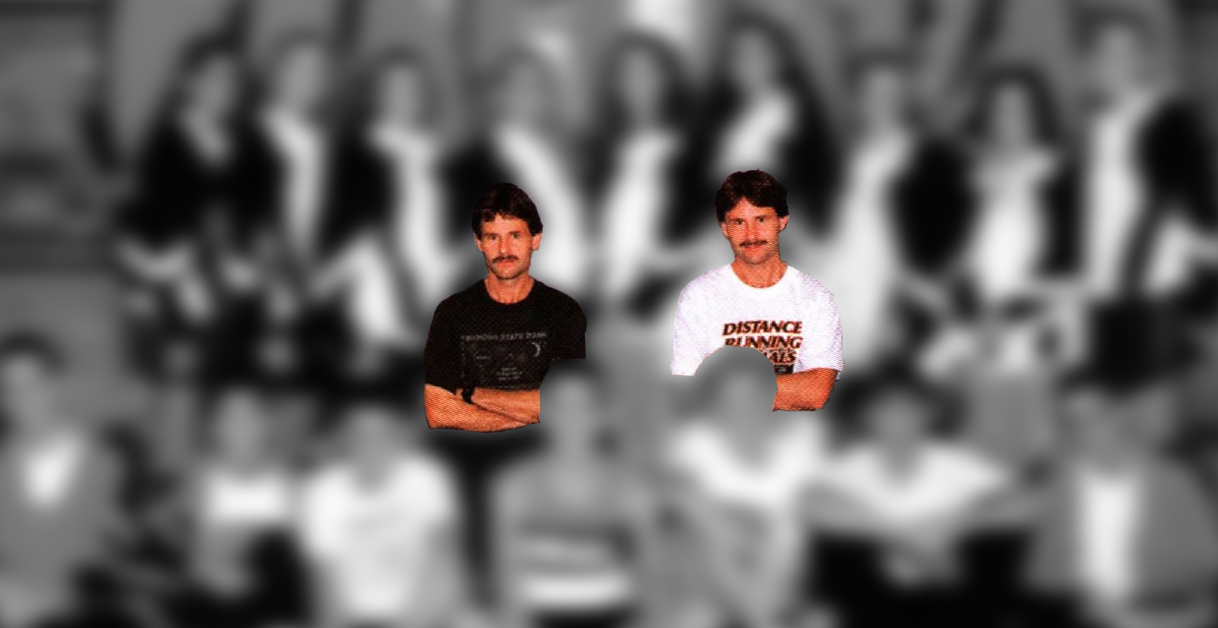

Visually, the twins were nearly indistinguishable, but in terms of strengths and experiences, they were markedly different.

Different in motivation:

Den began running in his sophomore year of high school because he was “a chubby little thing,” and he hoped exercising and transitioning to drinking Tab soda would help.

Tom has a “bizarre memory,” vividly recalling his brother running “hundreds of short little laps” with the floodlights on in their backyard.

Den’s backyard loop required seventeen laps to complete just one mile.

Tom would opt out of running for the majority of his high school career.

Difference in results:

In his first cross country race, Den emerged as the team’s second-fastest runner. “And so I stuck with it,” Den said.

Seeing his older twin brother’s accomplishments ignited Tom’s competitive spirit, prompting him to give running a try as well.

“I thought, well, okay, I’m going to do this too,” Tom said. “I started right at the very end of the season. I ran one race, and I got literally dead last.”

Den continued running track in his junior year, while Tom chose not to. However, during the summer between their junior and senior years, Tom joined Den on his runs, gearing up to join the cross country team in the fall of his senior year.

But by the end of their senior year, the two were finishing together.

One of their fondest memories is a race where they “went straight to the lead together” as it was a really neat being the “twins up there,” Den said.

Those successes came without the guidance of a distance coach. At Breese Mater Dei High School, the twins had to serve as each other’s coach.

Their differing strengths and weaknesses allowed them to sharpen each other, to push each other to new personal bests.

Come the end of high school, “I wound up being the number two runner to [Den] in cross country as a senior, although I beat him twice,” Tom said.

“I think it might have been the only race that our dad couldn’t make it to and Tom beat me for the first time,” Den said. “I wasn’t very happy about that.”

One would think that competitive spirit would have a chance to flourish with the opening of Normal West High School in ’95 when Den became the Wildcats ’ coach.

The brothers had a storied history as rivals. A childhood Ping-Pong match ended with Den receiving a paddle to the eye after defeating Tom 21-3.

The well-being of Unit 5’s Distance Running Animals led the brothers down different paths. They weren’t rivals. They didn’t want to compete. They wanted to enrich the runners of both high schools. With some of their runners transferring to the West, it was only natural for Den to go with them. The pack would stay together, just in modified form.

Courtesy: Reverie Yearbook

“We worked hard on trying to maintain, not just a relationship between the two of us, but also try to keep the kids connected,” Tom said.

“And even though they were at different schools, that there was a camaraderie and a sharing of interest and concern for each other, rather than trying to be enemies.”

This joint effort to improve together, even from separate schools, was crucial for the athletes’ success. Much like animals hunting in packs, Distance Running Animals chase their personal records in unison despite wearing different jerseys.

Every athlete aims to get faster with each race. When one sets a personal record, rivals cheer too, understanding the grind, the effort behind the achievement.

“That’s the great thing about coaching distance running is that you can have kids who are national class and you can have kids that can barely make it a lap around that track without it killing them,” Tom said.

“But no matter what level they’re at if they are willing to commit to it and be animals for themselves they can get better and have some sense of accomplishment.”

You can measure their legacy in time: 37 seasons.

In accolades and achievements, in Intercity and Big 12 conference titles, in state qualifiers and state medals.

In the stopwatches they’ve worn, their coaching career spanning ten generations of timers.

You can measure it in the tees and hoodies they still wear from their early coaching days, now worn thin and full of holes.

You can measure it by the boxes of practice plans in Tom’s basement, containing enough workout variations to design countless training programs, to run practices for another four decades.

Their legacy is more than miles.

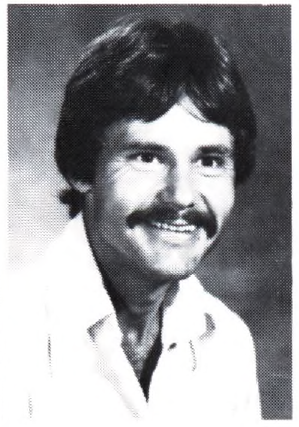

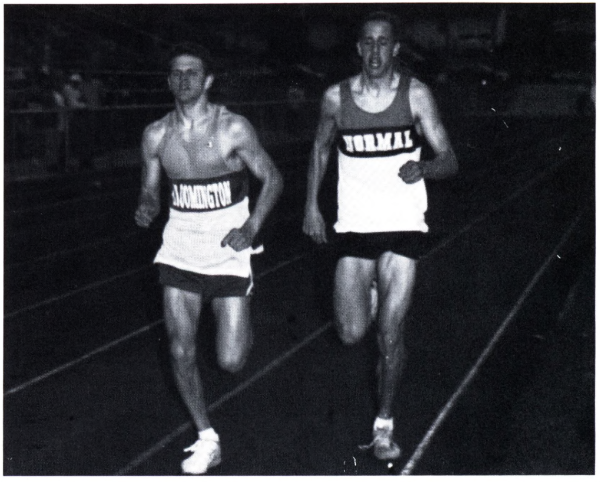

Their coaching career has spanned decades, providing them with exhilarating races to recount–Elliott Nott’s 1993 state win in the mile with a time of 4:16.52, the boys’ 4×800 meter relay’s second-place state finish in 1995…

Image Courtesy: Reverie Yearbook

And although these performances were immensely rewarding, the coaches believe success in the sport goes far beyond earning a state medal.

“As rewarding as those are,” Den said, “it’s also equally as rewarding just to see anybody have success. Anytime somebody PRs, it’s an accomplishment. That is one of the great things about running—you get that sense of personal improvement.”

“You can’t measure that in soccer or football or even basketball. It’s just something unique about timed sports,” Den said. “As a coach, thats what is so rewarding, getting to see that personal improvement.”

Ask a Patten, and they can likely tell you the season bests, the personal bests from athletes who long graduated.

The animals, Tom said, “are, quote-unquote, our family,” Tom said, “at least for four years.”

That’s can be the worst part of the job the brothers have done mostly on a volunteer basis for a decade.

“Over the course of four years,” Tom said, “you develop these attachments with kids. And then, as it is in life, they go off, and you rarely are able to maintain lifelong connections.”

But its about the journey, not the destination. Those four years really matter for those four years.

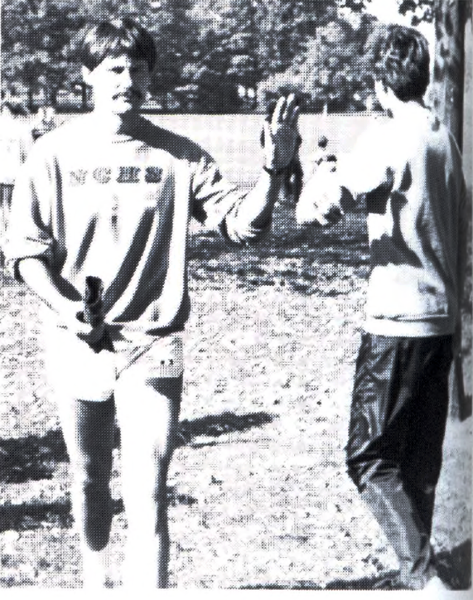

“Getting to interact with the runners before we get going and then after we are done are really some of my favorite parts of practice,” Den said. “That’s where you really get to feel like you’re getting to know people.”

Image Courtesy: Reverie Yearbook

“I really try to make sure that I talk to everybody every day,” Tom said. “Even if it’s just a little ‘good job’ or ‘how was school today’…I just think it’s essential. If you’re going to be in charge of a group, then it’s important that the people in the group know that you really care about each and every one of them.”

Their legacy is more than miles.

But the miles matter too.

At 69, it is clear the miles have had an impact on the twins’ bodies, they bear the scars of a hip replacement, a metal plate supports a wrist broken falling on a run…

But still the original Distance Running Animals endure.

When they aren’t preparing their runners for a trip around Eastern’s blue oval, the two are most likely out on a run of their own.

As next-door neighbors, the brothers are often together on their daily workouts: Den logs 50 miles a week, and Tom racks up 70.

From their first race to that grueling 1975 relay, the Patten twins have always embodied the spirit of Distance Running Animals. Their journey, marked by perseverance and brotherhood, echoes through the years. As they continue to inspire and lead, their story remains a beacon for those who dare to push the limits of endurance, reminding us all of the strength found in unity and the relentless pursuit of excellence.”

In 1975, three young men pushed their bodies to the brink in a quest for a world record. Though they fell short, the Patten twins’ legacy of determination and camaraderie was set in motion.

The original Distance Running Animals, Tom and Den Patten, have carved a path marked by passion and persistence.

Their legacy isn’t just in the races won or the records set; it goes beyond the trials and triumphs of the track and lives in the hearts of the runners they’ve mentored.

Every stride is a silent testament to the joy found in the run and the relationships. It is the relationships that make the miles matter.

If you value the Inkspot’s commitment to student journalism—giving Normal Community’s reporters real-world experience—please consider donating to support our staff’s trip to the National High School Journalism Convention.

Your generosity helps us cover travel costs, enter national contests and attend sessions led by top media professionals—an unforgettable opportunity to learn, grow, and represent Community on a national stage.

THANK YOU for investing in the next generation of storytellers.

![Community honors longtime coach Mr. Bryan Thomas before Oct. 3 game [photo gallery]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Thomas-6-1200x1200.jpg)

![Ironmen volleball head coach Ms. Christine Konopasek recorded her 400th career victory Oct. 21 as the Ironmen closed their regular season with a 2-0 sweep over Danville.

[Photo Illustration]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Vball400Thumb.png)

![Halloween candy cross section quiz [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Candy-cover-big-900x675.png)

![Average Jonah? [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/average-jonah-900x600.png)

![[Photo Illustration]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/trigger-words-1.png)

![Week 9: Coach Drengwitz on Week 8’s win, previewing Peoria High [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/W9_PeoriaThumb.png)

![Postgame: Drengwitz on Community’s 56-6 win over Champaign Centennial; staying unbeaten in Big 12 [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/10.17_FBwChampCent56-6_POST_thumb.png)

![Week 7: Coach Drengwitz recaps the Ironmen’s win over Bloomington, talks Danville [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Vikings-feature-Image-1200x675.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Halloween [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/tot-Halloween-YT-1200x675.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Fall favorites [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/ots-fall-web-1200x800.png)

![On the Spot – Teachers tested on 2023’s hottest words [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/On-the-Spot-Teachers-tested-1200x675.png)