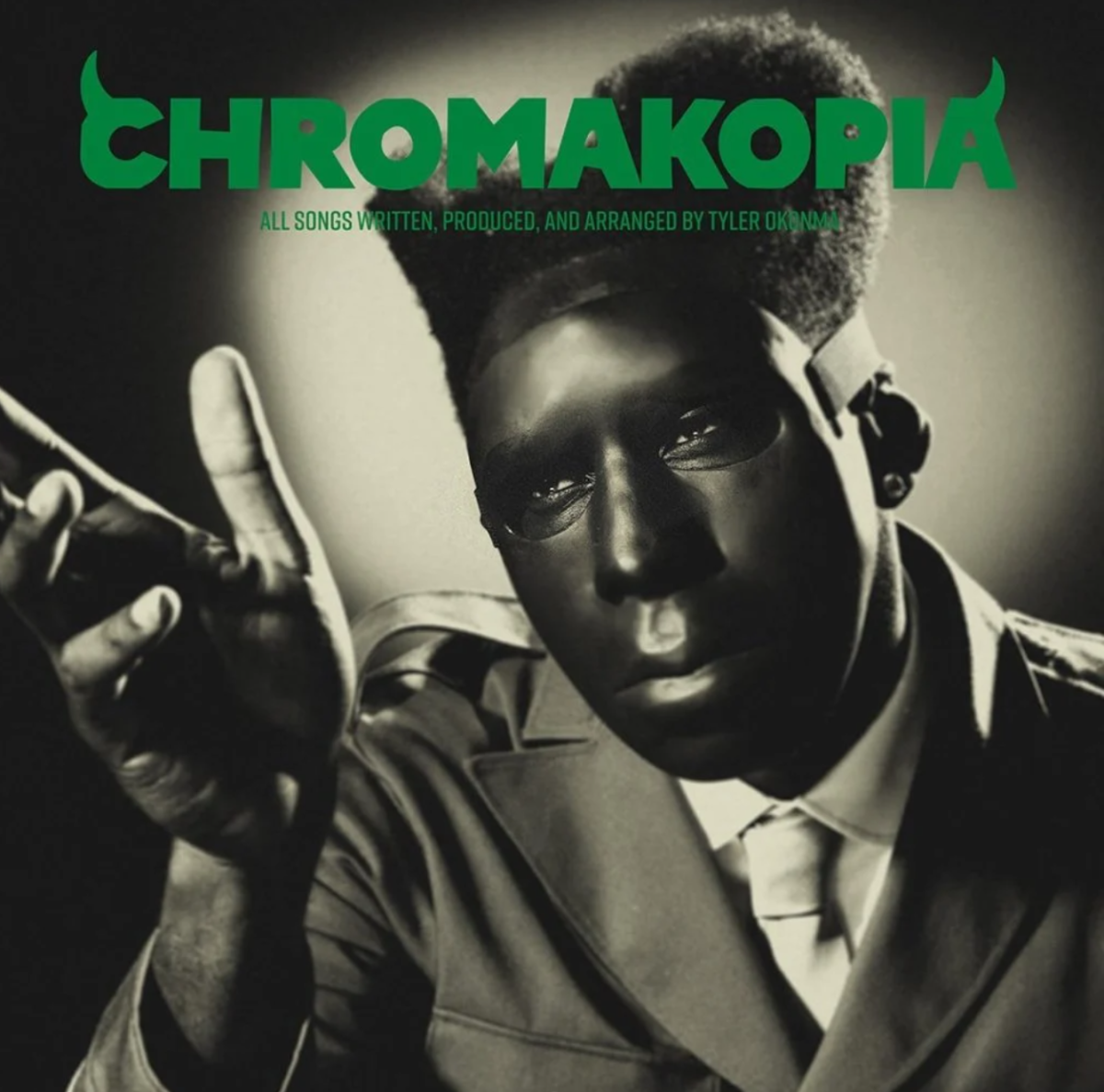

Ever wonder what high school courses Wednesday Addams or Miles Morales would take?

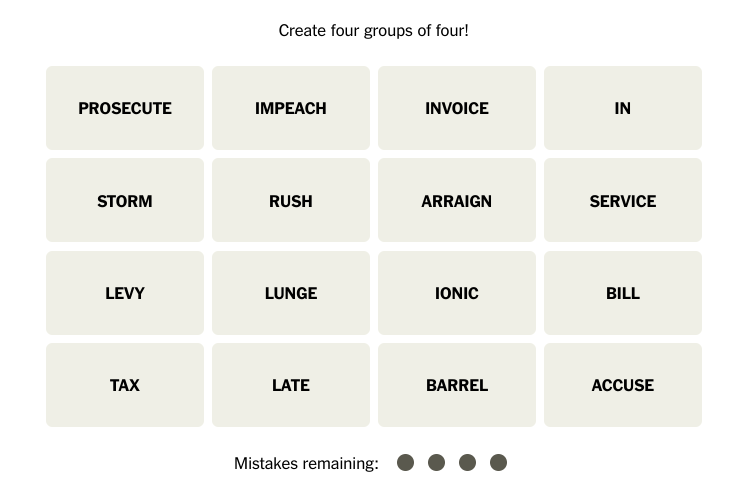

That’s the premise behind College Board’s new social media campaign.

Screenshot: College Board Instagram // @collegeboard; Twilight Image Still // Lionsgate Films

Amidst posts on financial aid and SAT practice problems, fictional characters are now the subject of an inquiry: What Advanced Placement courses would this pop culture figure—from Barbies to Miguel Rivera of “Coco”—take?

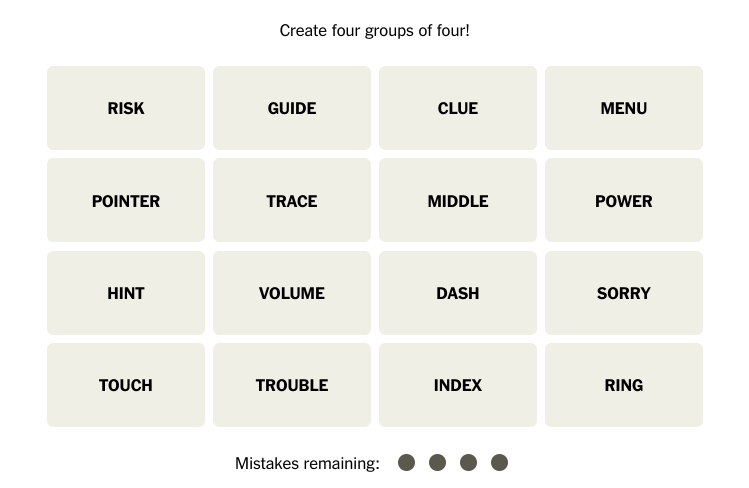

Teenage vampire Edward Cullen from “Twilight” might enroll in AP Psychology, Spanish or Biology.

But if Edward were a Florida resident rather than a fictional character from Forks, Washington, he would have experienced the looming threat of an AP Psychology ban in the southern state.

Last March, Florida passed the Parental Rights in Education Act, prohibiting the discussion of gender and sexuality in kindergarten through eighth-grade classrooms. Instruction on the topics is only permitted in high schools when “required by state academic standards” or as part of a health course students may opt out of.

The controversy around the legislation deepened this summer when the Florida Board of Education approved disciplinary procedures for teachers who violate the act dubbed the “Don’t Say Gay” law by its opponents. Teachers who taught gender and sexuality in AP—an elective course—would risk losing their teaching certificate.

Twilight Image // Lionsgate Films

On Aug. 3, College Board fired back.

The organization issued a statement declaring that “any course that censors required course content”—including the effects of sex and gender on development—“cannot be labeled ‘AP’ or ‘Advanced Placement.’”

To keep AP Psychology in course catalogs, the Florida Board of Education reversed its decision.

In most schools that previously offered the class, Floridian students are scheduled to take the comprehensive course as they have known it for the past 30 years.

But the fact the course was ever in peril—not to mention the restrictions still in place for non-AP classes—is cause for continued concern.

The controversy has made waves beyond the Atlantic coast, scoring a place in headlines, social media feeds and discussions across the country—including over 1,000 miles away in Bloomington-Normal.

To Community AP Psych teacher Mr. Patrick Lawler, eliminating the introductory psychology course would mean losing the social studies department’s “unique little jewel of a class.”

As the most popular social studies elective at Community, Lawler said, the course is more conducive to “personal connections” than classes like U.S. History or Regional World Studies.

Based wholly on people and how they interact, the content students learn in Psych is perhaps more broadly applicable than any other course’s curriculum—with uses in classrooms and life beyond Community.

“It seems to be a glue for kids in college,” Lawler said, “connecting things.”

Recent Community graduate Sid Sundarakrishnan (’23) has used that glue when asked to complete character analyses in his English classes.

After taking AP Psychology last spring—and enjoying it so much that he opted to observe the class for a semester-long education internship—Sundarakrishnan can quickly pull terms from psychology to explain characters’ behaviors.

“If I hadn’t taken AP Psych,” Sundarakrishnan said, “I wouldn’t be able to add the same level of depth to the character.”

Senior Shreya Bhatia—who took the class as a junior last year—said that taking AP Psych has also reaffirmed her intention to major in psychology on a pre-med track next fall.

“Not only did it further my need for more psych after this class,” Bhatia said, “but it gave me a good perspective of how I could use psychology in my day-to-day life.”

The course doesn’t just appeal to the researcher or future med student in Bhatia, but the human being: “someone who wants to understand what our culture and society is like.”

Someone we should all aspire to be.

Remove this student favorite from high schools and that understanding is lost.

The Florida Board of Education would argue that these benefits could still be appreciated in the absence of contested gender- and sexuality-related content.

The Florida BOE never wanted AP Psychology eliminated. Many of its members’ children would miss out on GPA-boosting and money-saving opportunities for credit without the class, after all.

In the Florida Board’s perfect world, AP Psychology would still exist—just without the instruction on gender and sexuality that the College Board whisked away that ‘AP’ label over.

But can a psychology course—meant to study human thought processes and behavior—be considered psychology if it neglects to address such integral parts of how we think and act?

The answer is a resounding no.

Bhatia said without discussion on gender, sexuality and race—another taboo topic in Florida classrooms—students can’t “truly understand personality, behavior and some of the other topics.”

Emma Carroll (’23), who also took AP Psychology from Lawler last year, said the content omission would leave out “crucial information” regarding research techniques: a premise to which the course devotes its entire first unit, “Scientific Foundations of Psychology,” and continues to build on every unit thereafter.

Students must learn about gender and sexuality “in order to fully grasp the past experiments that were done,” Carroll said—particularly those that analyze gender roles.

Because these topics are so ingrained in the course, cutting out content on gender and sexual orientation is a complicated undertaking that doesn’t mean cleanly clipping away a unit or two.

In fact, there is no unit specifically about gender and sexual orientation in the AP Psych curriculum, Lawler said.

The topics, Lawler said, come up “organically”—like in a mid-biology unit discussion on how genetics impact sexual orientation.

Ban those natural talking points, and heading the class could quickly mean jeopardizing a teaching license for Florida employees.

“You can’t mention your sexual orientation,” Lawler said. “Wouldn’t that also include straight people? Straight is a sexual orientation, so I’m violating that if I mention my wife.”

Lawler raises a strong point. The law is messy, easily contested with technicalities, and it makes teaching a course in compliance with the law—especially a non-AP course that doesn’t have College Board to defend it—nearly impossible.

For him to mention his wife technically would be in violation of a law preventing discussion on sexual orientation; his doing so does not expressly correspond with a state standard.

But the likelihood of the Florida Board of Education taking offense to the reference, of punishing Lawler?

Extremely low.

What representative, especially in a state so adamantly supportive of family values, would be caught challenging such a universally accepted premise as a man alluding to his wife?

As soon as it becomes a man referencing a husband or a woman referencing a wife, though—not to mention a student or teacher hinting at a preferred pronoun—the BOE’s supporters take offense.

There is no denying that the most staunch advocates for censorship in classrooms—those backing the BOE’s proposed limitations on the AP Psych curriculum—disproportionately oppose LGBTQ+ content.

One censorship-driven Twitter account boasting over 2.6 million followers, @LibsofTikTok, specifically publicizes the personal information of queer teachers and other LGBTQ-supportive staff members. From educators promoting LGBTQ books online to those simply hanging pride flags in their classrooms, founder Chaya Raichak said the call-outs are designed to prevent “the sexualization of children in public schools.”

The description echoes Florida Governor Ron DeSantis’ comments upon signing the Parental Rights in Education bill, the bill laying the foundation for challenges to AP Psych, almost verbatim: “Parents… should be protected from schools using classroom instruction to sexualize their kids.”

But those efforts to protect children have done nothing but endanger them.

Over two dozen LGBTQ-inclusive schools and libraries have received bomb and death threats after being posted on Libs of Tiktok, forcing children to evacuate and LGBTQ+ staff members to live in fear.

A consequence endured by no other group for merely promoting literature or mentioning a spouse.

The result of omitting gender and sexuality from the AP Psych curriculum is more than just a unit lacking context, then.

The double standard is yet another attack on the LGBTQ+ community.

The ban on gender and sexual orientation is, essentially, a ban on genders that are not cisgender and sexual orientations that are not straight.

Ban or no ban, gender and sexuality will always form “a significant part of who people are,” Lawler said— and “you can’t pick and choose what aspects of people are worthy of inclusion and what aspects aren’t.”

By implementing legislation that can be weaponized against LGBTQ+ students’ gender identities and sexual orientations, Lawler said, “you’re marginalizing a group that’s already marginalized even further.”

Lawler pointed to the fact that 45 percent of LGBTQ+ youth considered attempting suicide in the past year, according to the Trevor Project—a number for which insufficient representation and acceptance is to blame.

“When you never get a chance to see yourself reflected in the school,” Lawler said, “it puts you at a much higher risk for those situations.”

Take those opportunities for visibility out of AP Psychology—one of few high school courses that does discuss the LGBTQ+ community—and that risk only climbs.

But in a world where censorship in the form of book bans and entire school curricula looms, Lawler said he’s “never had more faith in young people to recognize the dangers… and to not just put up with it, but to actually stand for one another cohesively.”

The fate of course restrictions, Bhatia agrees, “will be up to the future kids who decide to fight.”

Because just as censorship was a problem well before the AP Psych dilemma, it will continue to pose issues well into the future.

Before it was AP Psych, Lawler said, it was textbook companies changing content on slavery and racism to appease a few states—and a few people in those states, at that.

And after the psych issue, AP African American Studies—a soon-to-be-released course Florida actually did ban in a letter claiming the class “significantly lacks educational value”—will be subject to similar debates.

But when students take initiative and fight against these restrictions, they have the power to fight against fear—an emotion Carroll called the product of misinformation.

“To restrict what people can learn about themselves and about this country that they live in,” Caroll said, “is scary.”

She’s right.

However scary it may be to publicly oppose authority figures, incomplete education is scarier.

So let recent threats to AP Psychology scare you enough to make your voice heard on the issue.

Just don’t let them psych you out.

![Community honors longtime coach Mr. Bryan Thomas before Oct. 3 game [photo gallery]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Thomas-6-1200x1200.jpg)

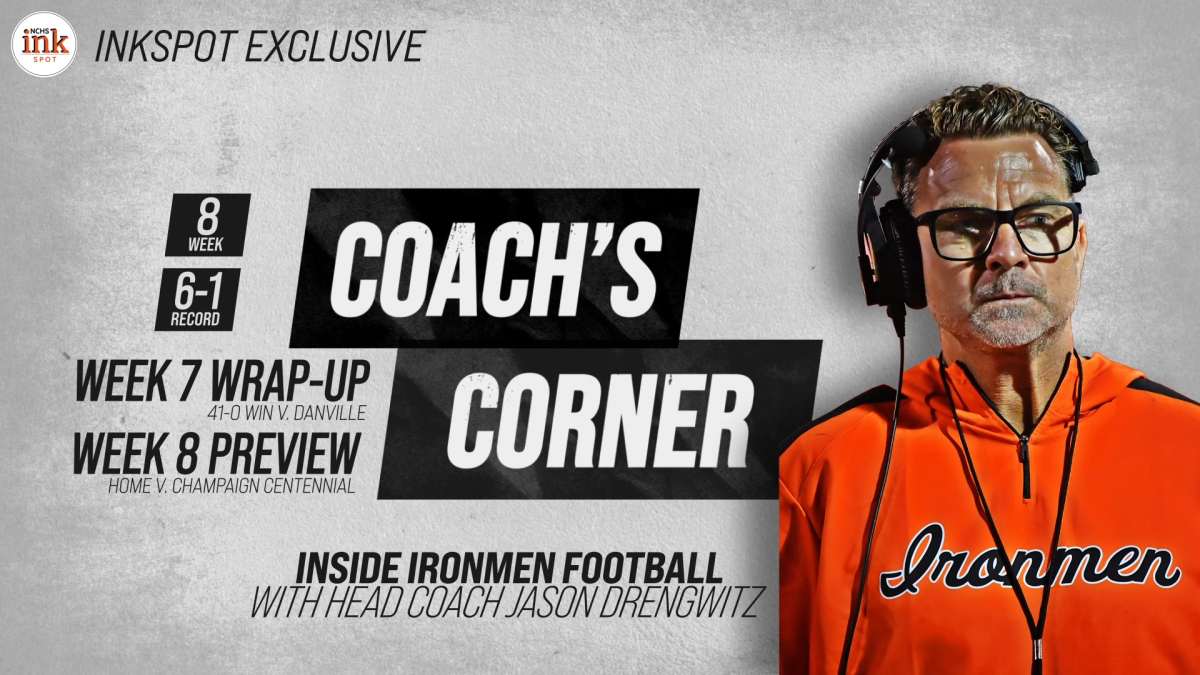

![Postgame: Drengwitz on Community’s 56-6 win over Champaign Centennial; staying unbeaten in Big 12 [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/10.17_FBwChampCent56-6_POST_thumb.png)

![Halloween candy cross section quiz [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Candy-cover-big-900x675.png)

![Average Jonah? [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/average-jonah-900x600.png)

![Week 7: Coach Drengwitz recaps the Ironmen’s win over Bloomington, talks Danville [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Vikings-feature-Image-1200x675.png)

![Week 5: Coach Drengwitz previews the Ironmen’s matchup vs. Peoria Manual, recaps Week 4 [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Week-5-v-Rams-1200x675.png)

![Postgame reaction: Coach Drengwitz on Community’s 28-17 Loss to Kankakee [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Week-4-postgame--1200x675.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Halloween [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/tot-Halloween-YT-1200x675.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Fall favorites [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/ots-fall-web-1200x800.png)

![On the Spot – Teachers tested on 2023’s hottest words [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/On-the-Spot-Teachers-tested-1200x675.png)