A tug on the sleeve. An adjustment of the arm.

Millions are turning to the needle to feed their addiction.

This is the vinyl revival. Vinyl records outsold CDs in the US for the first time in over 35 years, according to the Recording Industry Association of America’s annual revenue report.

Climbing steadily during the last 16 years, vinyl now accounts for over 70 percent of all physical music purchases, according to the RIAA report.

But why?

Digital music has never been more accessible, millions and millions of songs available at the push of a button.

Spotify alone boasts a catalog of over 100 millions tracks, literal lifetimes’ worth of music.

The average vinyl? 20 minutes per side.

And yet, record sales are seeing a major resurgence.

Mr. Stefen Robinson, who has been collecting vinyl since 2004, attributes the record renaissance to the fact that “streaming is just so disposable.”

Robinson’s collection of analog music, shelves of CDs and vinyl, by comparison is tangible, something he thinks “makes appreciating the art more… visceral.”

“What I like about listening to music via vinyl,” Robinson said, “is the intentionality of it. It requires a bit of effort to pick out something, to hold [it] in your hand to put on to the record player… something you spent time and resources to collect.”

“It’s like a ritual,” Robinson said. “It’s an experience where you have a more physical connection to the artist.”

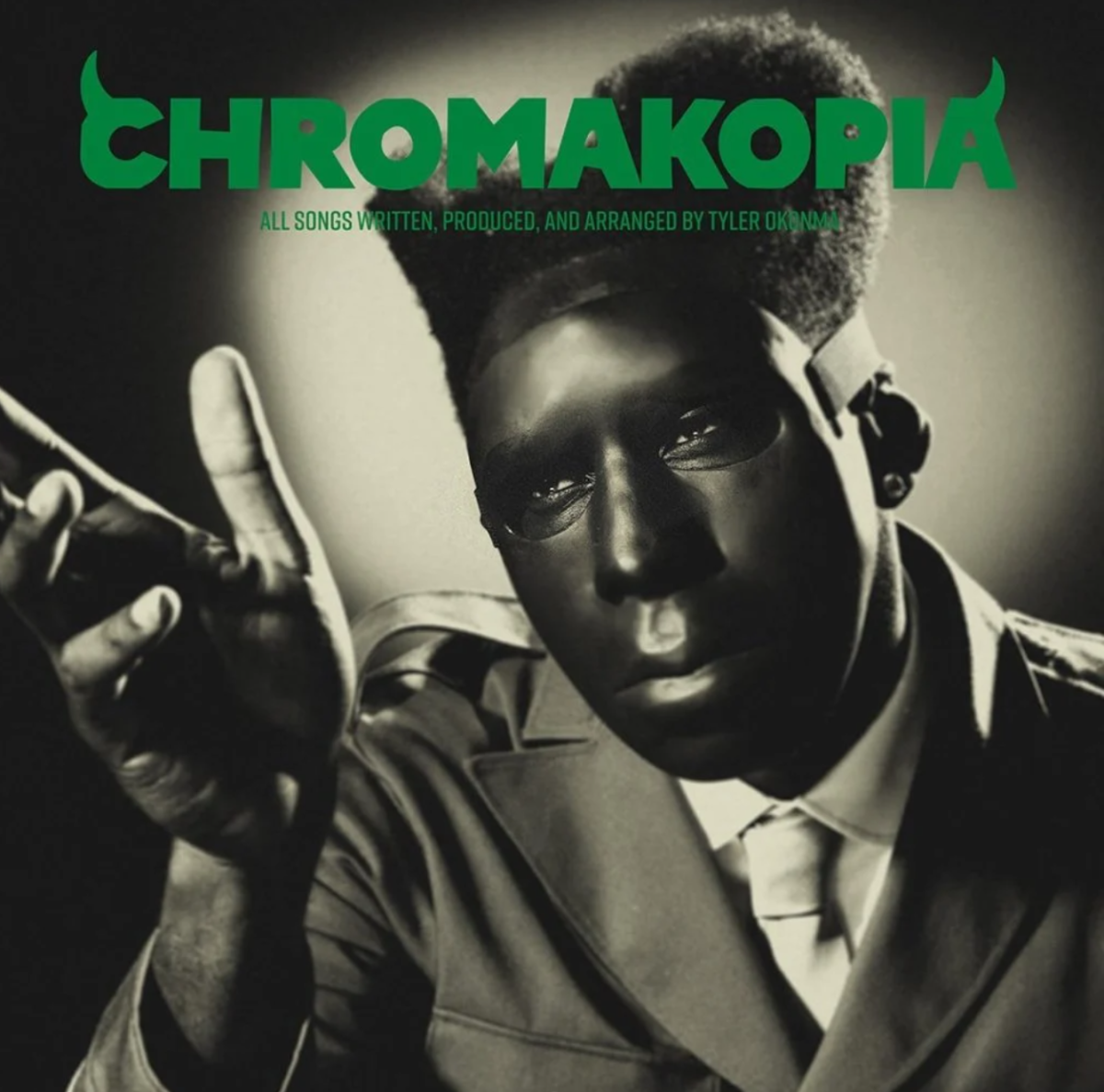

The record as a work of art, something carefully crafted and curated, a tracklist where one song seamlessly leads into the next. It’s that artistry that senior Parker Williams appreciates.

“Look at an album like ‘Folklore,’ ‘Evermore,’ some sort of concept album–‘Life of Pablo,’ ‘Dark Side of the Moon’…,” Williams said. “These are albums where the music is placed in a way where you have to experience it in full.

“The great thing about records is that you’re forced to sit down and do that,” Williams continued.

Robinson too prefers to listen to an album, start to finish, front to back.

But, Robinson said, “that doesn’t mean there isn’t a place for playlists.”

“I like occasionally listening to curated playlists, especially when a friend makes it for me,” Robinson said. “You know, that’s beautiful.”

Beauty–that’s what Williams finds in his collection of nearly 100 vinyls.

For the senior there is something alluring about the physical, tangible album that is missing with digital music.

There is the record sleeve and album cover –“if it’s a gatefold, you can have just beautiful artwork on the side,” Williams said.

There are the liner notes.

You can see the producers, the musicians, the lyrics, Williams said, “that’s one of my favorite things.”

There are multi-colored , one-off wax pressings.

“Buying a record you have all these other different layers,” Williams said, “you can have a fuller experience with records.”

“That makes a big difference to me in buying a record versus listening to it on Spotify.”

“I don’t hate streaming,” Williams said, it “is very convenient.”

“The great thing about living in today’s era,” Williams said, is the ability to listen to a single before the album is released, the ability to preview an album before purchasing it.

“You really want to know if an album is for you,” Williams said, “because records are really expensive.”

Junior Ean Hansen knows that expense all too well.

“I was at an Alice Cooper concert,” Hansen said, “and at the time, his newest album had just [been] released. He was selling them, signed.”

$80 later, Hansen left the concert with Cooper’s “Detroit Stories” (2021).

“Even though it’s not my favorite album,” Hansen said, “to me, it was worth it. Partially because I love him so much as an artist, but [also] I really wanted something physical,” a souvenir from seeing a favorite act play live.

Hansen’s vinyl collection, over 40 albums, exists, he said, as a physical representation of his love for a certain album or artist.

“To me, it’s worth it to have that physical [album], despite the price. Just the other day, I spent like 40-50 bucks on two vinyls.”

“You can still typically find good vinyl for about $20. As long as you know where to look, it’s easy to keep collecting at a reasonable price.”

By nature, Hansen is a collector. If he is passionate about it, he will collect it.

“I used to collect video games and video game consoles,” he said.

“Game Boys, Sega Genesis.” Funko Pops and San Francisco 49ers memorabilia.

And albums.

Hansen’s collection began after he found his dad’s record player and purchased his first album – Johnny Cash’s Greatest Hits.

“From there, it just kind of grew. I’ve upgraded my setup a few times, but it all started with just an old vinyl player and Johnny Cash,” Hansen said.

Beyond cash, beyond the price of albums, an issue with record collecting Hansen said, is availability.

“It’s harder to find vinyl,” Hansen said, by “artists who never got super successful. My favorite band of all time is Toto.

“You’ll find ‘IV’ sometimes because that has ‘Africa’ on it.”

The band’s other 13 studio albums?

“They just stopped reprinting them. It can be very difficult if you like less popular bands to find [them on] vinyl,” Hansen said.

“It’s easier for artists to release things on CD today than it is on vinyl,” Robinson, a musician, producer, and record label founder, said. “Vinyl is very expensive. It takes a long time to get it manufactured because there aren’t as many [manufacturers now]. They’re coming back. But, there are so many big name artists that are pressing so much stuff on vinyl, that independent artists and independent record labels have a hard time doing it in a way that’s cost-effective.”

That, Hansen thinks, is a shame because “vinyl will typically sound better than Spotify.”

It was that sound quality that got Williams started collecting vinyl when he heard his twin sister playing the Charlie Brown Christmas album.

“The sound was really good,“ Williams said–the reverb and echo on the children’s vocals, it was “just great stuff.”

An album on vinyl, Brighton Blackwell said, just has a cooler sound.

Blackwell began building her collection of around 35 records three years ago, something she attributes to her attraction to “old-timey things.”

This is something Williams understands.

A record, Williams said, is like “owning a piece of history. They’re like fragments in time.”

“I think that’s what makes collecting amazing,” Williams said, “because it is just history.”

The older, the better, because for Williams, buying “records is like old-school music discovery.”

“You only know one track on the album, you don’t know any of the other tracks. And then eventually, you’re like, ‘Oh, this is a great track.’ ‘I love this track.’

“That’s how I’ve gotten into a lot of artists,” Williams said.

Lynyrd Skynyrd. Little Richard. Miles Davis. Pink Floyd. Mötley Crüe.

“I think it really helps you expand your musical tastes,” because listening to a new album in its entirety, Williams said, “forces you to actually try something new.”

With digital “yeah, the songs right here, but I have all these other options that I know. You’re probably going to go with what you know.”

“It doesn’t matter where you start,” Williams said,–Bloomington Normal stores like Reckless Saint, North Street Records, Waiting Room Records, Reverberation–“find what you love, collect what you love.”

![Community honors longtime coach Mr. Bryan Thomas before Oct. 3 game [photo gallery]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Thomas-6-1200x1200.jpg)

![Week 7: Coach Drengwitz recaps the Ironmen’s win over Bloomington, talks Danville [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Vikings-feature-Image-1200x675.png)

![Halloween candy cross section quiz [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Candy-cover-big-900x675.png)

![Average Jonah? [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/average-jonah-900x600.png)

![[Photo Illustration]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/trigger-words.png)

![Week 5: Coach Drengwitz previews the Ironmen’s matchup vs. Peoria Manual, recaps Week 4 [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Week-5-v-Rams-1200x675.png)

![Postgame reaction: Coach Drengwitz on Community’s 28-17 Loss to Kankakee [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Week-4-postgame--1200x675.png)

![Week 4: Coach Drengwitz previews the Ironmen’s matchup vs. Kankakee [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ironmen-v-Kankakee-video-1200x1200.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Halloween [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/tot-Halloween-YT-1200x675.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Fall favorites [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/ots-fall-web-1200x800.png)

![On the Spot – Teachers tested on 2023’s hottest words [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/On-the-Spot-Teachers-tested-1200x675.png)