When “Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse” recently hit Netflix, the movie recaptured the hearts of audiences across the world as it took strides for diversity. Miles Morales and Gwen Stacy—the franchise’s first Black-Latino and female Spider-Mans—marked monumental moments for the industry.

Yet, some viewers might have missed what Pavitr Prabhakar, Mumbattan’s comedic crime-fighter, had to contribute to the conversation about inclusion and cultural awareness.

“What did you just say? Chai tea? Chai means ‘tea’, bro!” the Spider-Man exclaimed. “You are saying ‘tea tea’! Would I ask you for a ‘coffee coffee’ with room for ‘cream cream’?”

With just a few words, the teenager-turned-superhero dusts cobwebs off a linguistic notion: the bilingual tautology.

In plain English, bilingual tautologies are inherently repetitive phrases.

But nothing about English is plain. It’s 45 languages wrapped in one, the result of centuries of colonialism, imperialism—basically every “-ism” there is.

Like most languages, English grows by borrowing words. Ketchup is Chinese. Sofa, Arabic. The word dope? Definitely a dope word. . . it’s from the Dutch.

Don’t get me wrong—cultural exchange connects us all through a web of shared experiences, ideas and perspectives.

But a tautology isn’t an exchange; it only goes one way. You won’t hear the English word for mustard in China.

Sticky situations like these accidental redundancies arise when we don’t understand other languages enough to adopt their terms correctly. The meaning gets tangled up, paving the way for deeper cultural ignorance.

Phrases like ramen noodles and pesto sauce pop into existence. Ramen, which means “pulled noodles” in Japanese, is used to describe the word “noodles.”

While I do love a bowl of noodles noodles with sauce sauce, the redundancy makes my Spider-Sense tingle.

The fault, of course, doesn’t lie with any individual person. If we had to think about the etymology of every single thing we ate, we’d have a hard time eating at all.

While you don’t have to drastically alter your linguistic habits, simple switches from the terms “naan bread” and “queso cheese” to just “naan” and “queso” make us more self-aware and allow us to show cultural sensitivity.

With the great power we have as English speakers, comes great responsibility to attribute the various languages we borrowed from.

On a scale of one to catastrophic, tautologies lie solidly within the realm of not-that-bad.

But next time you swing into Olive Garden and order minestrone soup, here’s some food for thought: maybe drop a word.

![Community honors longtime coach Mr. Bryan Thomas before Oct. 3 game [photo gallery]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Thomas-6-1200x1200.jpg)

![Halloween candy cross section quiz [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Candy-cover-big-900x675.png)

![Average Jonah? [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/average-jonah-900x600.png)

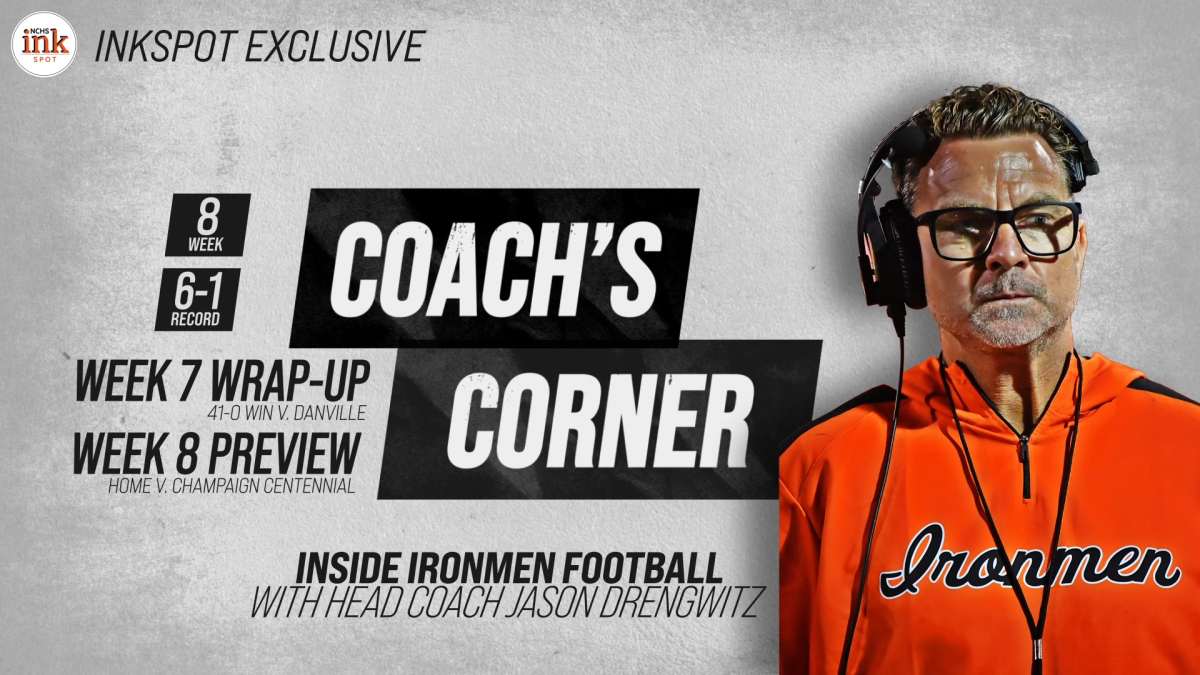

![Week 7: Coach Drengwitz recaps the Ironmen’s win over Bloomington, talks Danville [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Vikings-feature-Image-1200x675.png)

![Week 5: Coach Drengwitz previews the Ironmen’s matchup vs. Peoria Manual, recaps Week 4 [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Week-5-v-Rams-1200x675.png)

![Postgame reaction: Coach Drengwitz on Community’s 28-17 Loss to Kankakee [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Week-4-postgame--1200x675.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Halloween [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/tot-Halloween-YT-1200x675.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Fall favorites [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/ots-fall-web-1200x800.png)

![On the Spot – Teachers tested on 2023’s hottest words [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/On-the-Spot-Teachers-tested-1200x675.png)