At 6 a.m., before Community’s hallways fill with groggy students, Bode Thompson is already outside, scanning the tree line for movement. Fall migration is in full swing, and warblers—small, colorful birds that dart through the branches—are passing through.

Thompson, a senior, spends his mornings chasing birds before school and his evenings planning the next big trip. While his classmates scroll through social media, he has Ebird or Merlin open on his phone. When his classmates are sleeping in, he’s out in the field with a camera in the other, scanning the skies for the next rare find.

People think it’s an odd hobby, Thompson said, unfazed. “Like, I tell them, and they just kind of look at me, thinking ‘weird.’ But, I love birds, so I don’t really care.”

Birding, as he calls it, started as a way to stave off boredom during the pandemic. His mom set up a feeder, his dad picked up an old camera, snapping pictures of the birds in the backyard, and Thompson—then a self-proclaimed uninterested observer—got pulled in.

Thompson’s interest in birding came into focus when his dad convinced him to take a trip to a nearby park and handed him the camera.

At first, Thompson pointed and clicked, snapping blurry shots of leaves and empty branches. But as he adjusted the lens, tracking the flickering movement of tiny birds darting through the trees, something clicked.

Capturing a bird mid-flight, catching the exact moment it landed on a branch—it was like a puzzle, a test of patience and precision. The challenge of framing the perfect shot, of identifying the species through the viewfinder, turned what he thought was just a casual outing into something much more.

“It made me really like it,” Thompson said. “I really liked photography, and it was a challenge to take photos of little birds going all over the place.”

Suddenly, birdwatching wasn’t just about watching—it was about capturing, documenting and discovering.

And it wasn’t long before he was the one leading the charge, camera in hand, scanning the skies.

Now, he wakes up early for peak birding hours, sometimes balancing his passion with his responsibilities–soccer practice, his job, schoolwork…

Sometimes he leaves those responsibilities behind altogether.

“I’ve straight up just left school,” Thompson said. “I’ve left my job to go see a bird.”

If a rare bird is spotted anywhere near Central Illinois, Thompson said, he’ll be there.

Like the time a Ross’s Gull—a bird so rare it had only been spotted in Illinois a handful of times—showed up near Chicago.

Thompson didn’t hesitate.

“I just went to my boss and was like, ‘I have to leave. Please. Let me go,’” he said. “And she was like, ‘Okay, do all your stuff.’ I did like three hours of work in 20 minutes, then I was like, ‘All right, I’m out.’”

Thompson arrived just in time to see the bird, an experience he described as incredible.

By the next day, it had disappeared, and hasn’t been spotted near since.

“I was really glad I went,” Thompson said.

That wasn’t the first time—or the last—he went to extreme lengths for a sighting.

There was the PowerPoint presentation, carefully crafted to convince his dad to drive to Waukegan in the dead of winter to see a Small-billed Elaenia, a South American bird that had no business being in Illinois.

“It was the third-ever U.S. sighting,” Thompson said.

The Small-billed Elaenia trip was the one that started it all. He had read about the sighting in December 2021 and immediately started planning. His dad needed convincing, so Thompson got to work.

The thesis of the presentation: “Why it would be dumb if we didn’t go,” Thompson said.

It worked.

They made the trip, braving the frigid December air. After waiting 40 minutes, the bird finally appeared inside a fenced-in area.

Afterward, they explored the area, spotting other rare birds—like Long-tailed Ducks bobbing in the harbor.

“That was just really fun,” Thompson said. “That was kind of the first big trip I did.”

That first chase set the tone for the ones that followed. The next winter, Thompson was in Minnesota, where he saw eight Great Gray Owls—North America’s largest owl, and one of the hardest to find.

There are the four-trips to Minnesota’s Sax-Zim Bog, a hotspot for rare birds. On one, he chased a Fieldfare—a European species making its first recorded appearance in the Midwest.

That, Thompson said, was “a mega rarity. It was really random.”

There was the whirlwind 20-hour road trip one weekend.

When a White-winged Tern appeared in Michigan, Thompson trekked 10-hours just to see it.

“I had to call off work,” he said. “I got it. Drove back the same day—20-hour round trip. I had to walk two miles to actually find the bird. It was really cool.”

There’s the trip to Costa Rica to see the Great Green Macaw, “one bird that’s really close to being extinct,” Thompson said.

There are only a few hundred pairs left, Thompson said. “They’re critically endangered, and it’s not getting better.”

Unlike his usual birding trips, this didn’t require a presentation or convincing dad, it required secrecy.

“I had to go through a lot of people to figure out where it was,” he said. “Because they were hidden—people are trying to catch them to sell them.”

Poachers target the macaws, Thompson said, selling them for thousands of dollars.

In a country where capturing and selling exotic birds is a way to survive, information on their whereabouts isn’t handed out freely.

In Costa Rica, Thompson said, one of his bird guides used to be a bird trapper, selling the animals on the black market.

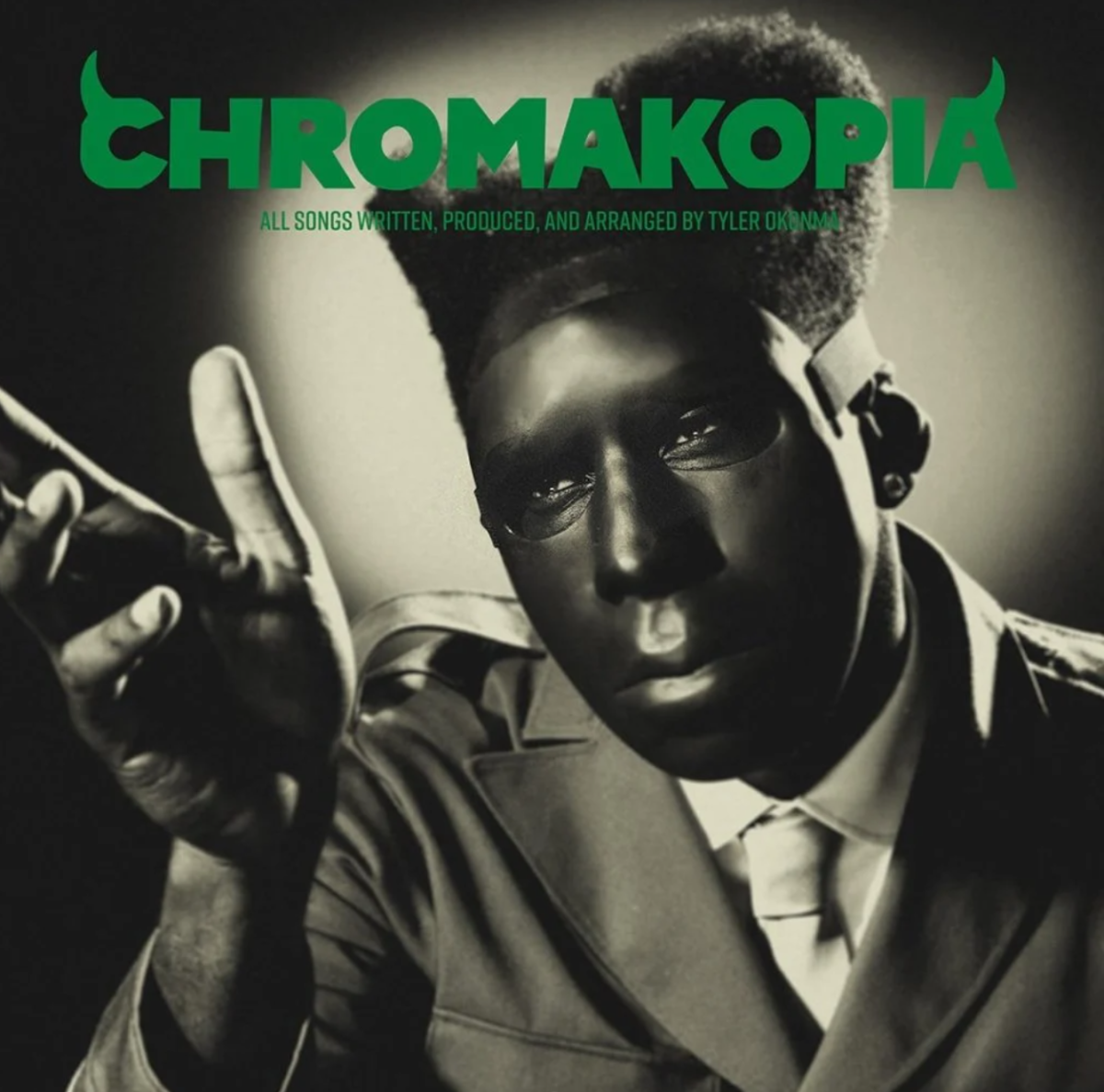

Photo Courtesy of: Bode Thompson

He had to find his own way in.

“I looked at eBird, found names of people reporting stuff, looked them up on Facebook, sent them messages,” he said. “I’d do that to like 30 people until I got a response.”

His networking paid off. He mapped out where to go, who to contact and even how much everything would cost.

“I told my dad, ‘This is where we’re gonna go, this is what we’re gonna do, this is who we’re gonna go with, and this is how much it’ll cost,’” he said.

And when they arrived, he did what he always does—he got up at sunrise, birded until dark, then did it all over again the next day.

It isn’t just about the thrill of the chase, though, it goes well beyond that: birding is an escape for Thompson.

“When I’m doing it, I’m not thinking about school or stress,” he said. “I’m just focused on finding a bird.”

Birdwatching is shaping more than just Thompson’s weekends. As the youth director for the Grand Prairie Bird Alliance, the local Audubon Society, he leads bird walks and conservation projects, including building birdhouses for elementary schools.

Over the summer, he worked with Illinois State University banding house wrens—gently catching them, measuring their wings and tracking their migration patterns.

Birding has already taken Thompson across the country—and beyond—and he has no plans to stop.

His plan: ornithology, bird guiding, something that keeps him outside.

“Finding new stuff, that’s what I love,” he said. “That moment of spotting a rare bird, knowing you’re the first one to see it—it’s just awesome.”

![Week 5: Coach Drengwitz previews the Ironmen’s matchup vs. Peoria Manual, recaps Week 4 [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Week-5-v-Rams-1200x675.png)

![Halloween candy cross section quiz [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Candy-cover-big-900x675.png)

![Average Jonah? [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/average-jonah-900x600.png)

![[Photo Illustration]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/trigger-words.png)

![Postgame reaction: Coach Drengwitz on Community’s 28-17 Loss to Kankakee [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Week-4-postgame--1200x675.png)

![Week 4: Coach Drengwitz previews the Ironmen’s matchup vs. Kankakee [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ironmen-v-Kankakee-video-1200x1200.png)

![Week 3: Coach Drengwitz previews the Ironmen’s matchup vs. Urbana [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/week-3-web-1200x1200.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Halloween [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/tot-Halloween-YT-1200x675.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Fall favorites [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/ots-fall-web-1200x800.png)

![On the Spot – Teachers tested on 2023’s hottest words [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/On-the-Spot-Teachers-tested-1200x675.png)