Whether it’s another blowout victory under the Friday night lights or a tense, final-possession battle on the basketball hardwood, whether the roar of the crowd erupts in triumph or falls to an anxious hush, one constant cuts through the noise at Normal Community High School–the familiar, booming voice of Mr. Dana Starkey.

The business teacher’s role as the Ironmen’s public address announcer isn’t a side hustle, not a way for Starkey to earn some extra cash. It’s another chapter in a four-decade-long love story: Starkey’s lifelong romance with sports, with his hometown and with Ironmen athletics—a love story that began in the 1980s when a young Starkey attended his first Community football game.

Under the glow of the stadium lights, surrounded by the electric energy of the crowd, the junior high student fell for the high school.

In the shadow of Illinois State University, the blond-haired boy witnessed the legendary Dick Tharp at the helm of the Iron football program. The Iron would go 25-5 on the gridiron during Starkey’s years as a Chiddix Charger, a record that would only help his infatuation grow.

During that stretch on the basketball court, the Iron would never suffer a losing season.

The Iron’s athletic success during the formative years of the adolescent sports fan was more than just a series of wins—it was a source of pride, a shared identity and a constant reminder of what it meant to be part of the Normal community.

Each victory strengthened the connection, fueling a sense of belonging that extended beyond the scoreboard and into the fabric of Starkey’s admiration.

When Starkey entered high school in 1987, his love for the Ironmen was fully engrained.

In 40 years, a lot has changed. The Normal Community Starkey first fell in love with was an unairconditioned building on Kingsley Street. Unit 5 had just one high school. Raab Road was an endless sea of cornfields.

In the four decades since Community captured Starkey’s heart, traditions have been lost, new ones have emerged.

The old Normal Community building, now Kingsley Junior High, wouldn’t have airconditioned classrooms until 1993 when the building was remodeled. [Photo: Inkspot Archives]

But one thing has been a constant: Starkey’s Iron pride.

Ms. Amy Scott was Starkey’s high school classmate in the relic on Kingsley Street, a building built in 1929.

Together, in senior English, they endured the humid, sticky days. Even then, Scott said, in a classroom that felt like a furnace even in the fall, Starkey’s school pride radiated.

“In spite of the rundown conditions,” Scott said, “there was a lot of school spirit and a lot of positivity in the building.”

A source? Starkey–“The Boy Wonder.” That’s the moniker Scott and her friends affectionately dubbed Starkey at school.

He was smart, he was personable, Scott said; he seemed to excel at whatever he tried.

And, Scott said, “he had a lot of school spirit then.”

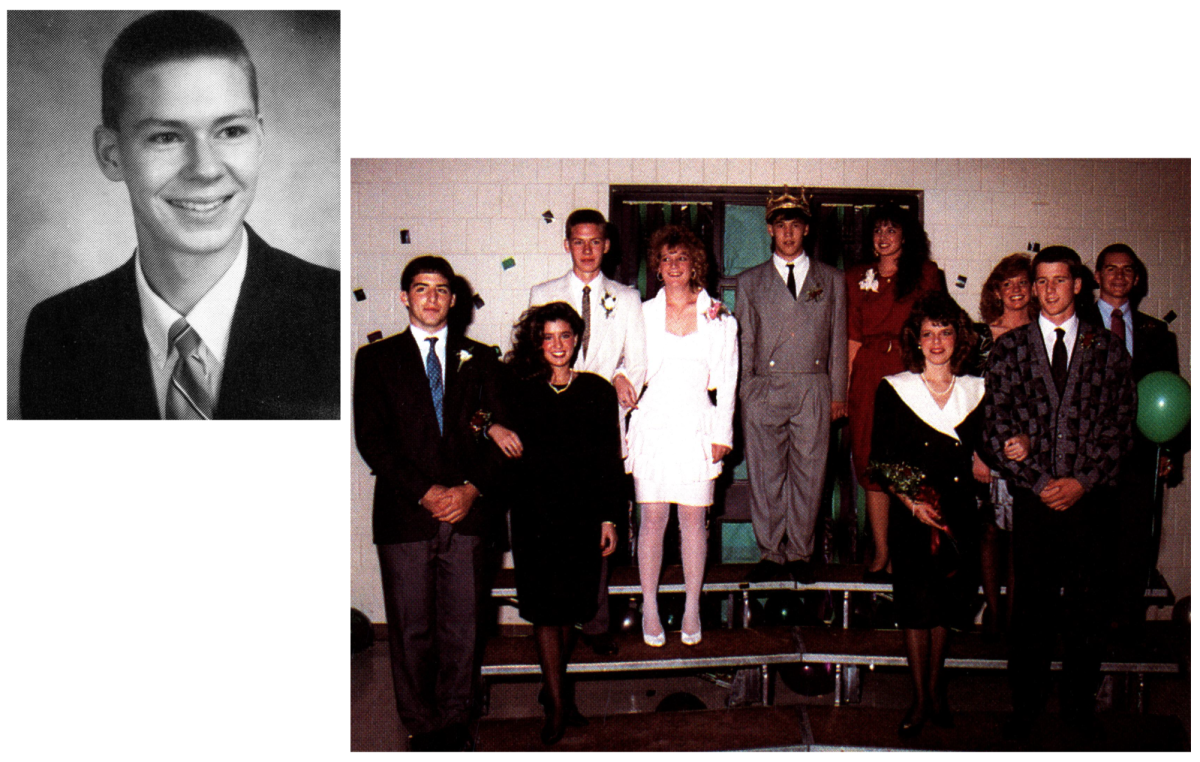

Image Courtesy of: The Reverie yearbook

Student Council, Junior class board, vice president of the Senior class–you name it, and the Boy Wonder was involved.

That involvement would earn him recognition–the annual Daughters of the American Revolution award, bestowed on students for exceptional dependability, leadership and service–and a spot on the homecoming court.

But the Boy Wonder was not without weakness.

“In high school, I loved sports,” Starkey said, but passion wasn’t enough to earn him a spot on a varsity roster.

The very thing that first attracted him to the Ironmen was something he could never achieve.

“I wasn’t a great athlete myself,” Starkey said.

Starkey’s struggles on the field never dampened his admiration; instead, they heightened his appreciation for the incredible talent surrounding him. To see what his classmates could do at the age of 16, 17 and 18, Starkey said, was awe-inspiring.

That sense of wonder, born out of his own limitations, instilled in Starkey a lasting respect for the athletes who carried the Ironmen’s legacy forward.

And while Starkey wouldn’t wear an Ironmen jersey, he still found other ways onto the field.

On a Friday night, as Community beat Bloomington on the gridiron, Starkey would beat the cadence of the school’s fight song, marching in step with the Iron drumline.

Come Homecoming Week, he’d trade his drumsticks for pom-poms, joining his senior classmates in full drag to cheer on the powderpuff players with the same energy he brought to every halftime show.

It was the end of the 1980s, the decade that saw Dustin Hoffman star in “Tootsie,” Tom Hanks in “Bosom Buddies,” and Starkey and his senior pals in the Seniorettes, an annual homecoming tradition. In oversized wigs, borrowed cheerleader uniforms and hastily applied makeup, the teenage boys twirled on the sidelines, performing exaggerated cheer routines.

In the 35 years since Starkey graduated, a lot has changed.

At the time, drag was a recurring pop culture trope: in 1982, Dustin Hoffman (Master Shifu in the “Kung Fu Panda” franchise) was nominated for a Best Actor Academy Award for his portrayal of actor Michael Dorsey, a man who disguises himself as a woman to land a role on a soap opera.

For two seasons on the sitcom “Bosom Buddies,” Tom Hanks (“Forrest Gump,” “Toy Story” franchise) played one of two friends who disguise themselves as women to secure affordable housing in a women-only apartment building.

Image Courtesy of: The Reverie yearbook

Some things never do.

“Most of what makes Mr. Starkey, who he is,” Scott said, “has stayed the same.”

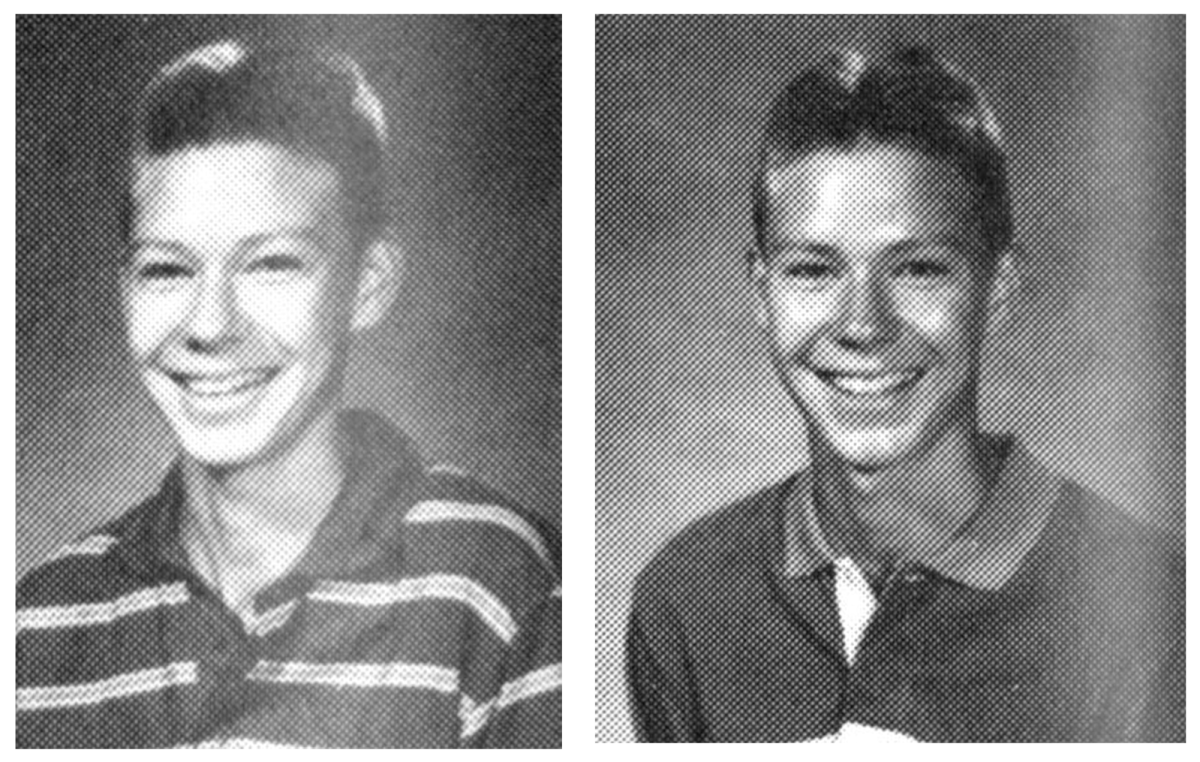

Sure, look at his sophomore and junior yearbook pictures, and that same boyish face remains; the signature polo shirt is there, too. But more than that–dedication, service, his love for the orange and black.

Image Courtesy of: The Reverie yearbook

After graduation, Starkey stayed close to home, attending Illinois State and Illinois Wesleyan. The proximity allowed him to keep one foot firmly planted in the Ironmen world, cheering from the stands and revisiting the fields and courts where his love for Community had first blossomed.

With a degree in business education, Starkey realized his ultimate dream in 1995: returning to Community as a teacher. For him, it was more than a career—it was a homecoming.

“I loved high school so much that I decided to become a teacher,” Starkey said.

But he didn’t want to teach anywhere–“I wanted to come back and be an Ironman.”

Starkey picked up where he left off.

The young teacher found countless ways to be involved with the school, whether working on the chain gang or assisting with freshman basketball.

Image Courtesy of: The Reverie yearbook

“I loved being on the sidelines, I loved being close” to the game, Starkey said.

His love for being close to the action eventually led him to the best seat in the house—behind the microphone.

What began in 1996 as a one-time gig announcing a boys’ basketball game quickly turned into a calling.

“I don’t know if I was the first choice or the fifth choice,” Starkey joked, “but [they] ended up asking me to do it… and I really enjoyed it.”

By 2005, Starkey had become the voice of Normal Community football and boys’ basketball, his resonant “First Down, Ironmen!” call ringing out over the football field for the past 20 years.

Announcing, Starkey said, brings out a childlike joy that feels as fresh as the days he first fell for Community. He is transported from calling the game above Dick Tharp Field to watching Dick Tharp coach.

Behind the mic, Starkey said, “I almost feel like I’m a little kid again”–a boy feeling wonder.

That’s an added perk of the gig. What truly drives Starkey to announce, he said, is it is a way to give back to the school that gave him so much.

“I feel like I’m providing a service to a school,” he said.

This summer, Starkey found himself in the position to provide that same service to another of his alma matters–Illinois State University.

Since Starkey first realized his love of announcing at Community games, it had been a dream, he said, to call the action in “a bigger venue.” But it was just that–a dream.

Until a phone call from someone at Illinois State.

The Redbirds’ Public Address announcer position had suddenly become vacant.

The Redbird football season was kicking off in just a few weeks.

The school needed an announcer, an experienced one–fast.

They’d heard great things about Starkey.

Would he come in for a tryout?

Some things change–dreams become reality.

“One second, you’re doing Normal Community,” now, ISU?

“My high school self would be really shocked,” Starkey said–in disbelief that he’d not only be behind the microphone for the Iron but the’ birds, too?

The Redbirds, the only team that rivals the Ironmen for a place in Starkey’s heart.

“My teenage years were the heyday of some really good ISU basketball teams,” Starkey said. “Some of my heroes were ISU basketball players”–the likes of Brad Duncan and Rickie Johnson, dominating in Horton Field House.

“Quite honestly, my 52-year-old self is quite shocked.”

Some things change, some things never do.

At Hancock Stadium, Starkey’s signature enthusiasm shines through.

His signature takes on a slightly different flourish–“First Down, Redbirds!” echoing over the sea of red and white the same way it has decades.

Things change.

These days, you won’t see the wooden bleachers in Horton Fieldhouse, once the roaring epicenter of Redbird basketball, shake under the weight of excited fans. ISU basketball moved under the soaring dome of Redbird Arena, now CEFCU Arena, while Starkey was still in high school.

Hancock Stadium isn’t as modest as it was when Starkey first became a Redbird fan–the facilities have undergone a transformation, much sleeker, more modern, expansive.

Some never do.

Starkey is close to where it all started, just a few hundred feet from where he first fell in love.

He is calling the names he’s announced over the stadium speakers for the last several seasons–Niekamp makes another game-changing play.

The uniform has changed, after making headlines as Ironmen, Ty and Dexter now suit up for the Redbirds.

But Starkey hasn’t.

Even as Starkey plans to retire from teaching in four years, his voice shows no signs of fading. Whether at Dick Tharp Field, in Hancock Stadium, in CEFCU Arena, Starkey’s passion for announcing—his love for the orange and black; the red and white; his alma maters; his hometown–remains as constant as ever.

Calling the names of students he’s had in class, knowing them both on and off the field—”that’s what makes it exciting,” Starkey said.

“I had Ty [Neikamp] for two years,” Starkey said. “It’s been a blast being able to call his name at ISU.”

Reflecting on his career, one of Starkey’s favorite moments: a game against the Bloomington Raiders, where Sam Smith secured an Ironmen victory with a game-saving interception.

“I had Sam in class for two years,” Starkey said. “When he intercepted the pass, the eruption of joy was unforgettable. As I called the play and yelled, ‘First Down, Ironmen!’ it was pure excitement.”

(Zachary Knox-Doyle)

![Community honors longtime coach Mr. Bryan Thomas before Oct. 3 game [photo gallery]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Thomas-6-1200x1200.jpg)

![Playoffs Rd. 1: Coach Drengwitz on Ironmen’s 7A playoff opener at Carmel Catholic [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/PW_PresserVCC_Thumb.png)

![Halloween candy cross section quiz [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Candy-cover-big-900x675.png)

![Average Jonah? [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/average-jonah-900x600.png)

![[Photo Illustration]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/trigger-words-1.png)

![Hauntcert performers on why this year’s show hits all the right notes [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Untitled-2.png)

![Ironmen volleball head coach Ms. Christine Konopasek recorded her 400th career victory Oct. 21 as the Ironmen closed their regular season with a 2-0 sweep over Danville.

[Photo Illustration]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Vball400Thumb.png)

![Week 9: Coach Drengwitz on Week 8’s win, previewing Peoria High [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/W9_PeoriaThumb.png)

![Postgame: Drengwitz on Community’s 56-6 win over Champaign Centennial; staying unbeaten in Big 12 [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/10.17_FBwChampCent56-6_POST_thumb.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Halloween [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/tot-Halloween-YT-1200x675.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Fall favorites [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/ots-fall-web-1200x800.png)

![On the Spot – Teachers tested on 2023’s hottest words [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/On-the-Spot-Teachers-tested-1200x675.png)