A new class of jittery sixth graders funneled into Chiddix Junior High, anxious to enter a foreign world: lockers and their dreaded combinations, too-short passing periods in crowded hallways and an eight-class, recess-less schedule.

Entering junior high: a nerve-wracking experience for every 11-year-old who’d just ordered their first PE clothes or practiced opening their lock for the hundredth time the night before.

But on Anna Fukomoto’s first day as a Charger in 2019, she felt those nerves tenfold.

Because for her, “foreign” meant more than unfamiliar.

While other middle schoolers’ school commutes were mere miles, short trips in the passenger seats of their parents’ Toyotas, Anna was over 6,000 miles from her own home: Toyota, Japan.

Anna’s father had landed a three-year contract with Toyo Tires in the U.S., propelling his three children—Anna and her two younger siblings—out of Japan’s uniformed corridors and into the lively hallways of American public school.

Braving those hallways on the first day would have been hard enough, Anna thought as she gazed out the window of her mom’s minivan at unfamiliar street signs.

Hard enough if her bus hadn’t skipped her stop, a complication that now found Anna long overdue for her first day at Chiddix.

Anna knew it would be a day of ‘firsts,’ and now her first junior high tardy joined the already-daunting list.

First tardy. First passing period. First American English class.

The adjustment wouldn’t be easy, but Anna’s excitement still peaked when the passing scenes outside her mom’s car slowed, a brick building coming into view.

“I wanted to go to the United States someday,” Anna said, reflecting on her childhood dream, “so I was happy.”

So happy to experience American life, Anna said, that saying goodbye to her Japanese friends didn’t feel sad at all. She knew she’d be back across the world soon enough.

But well before the final bell rang that first day, Anna could tell she wasn’t just attending school across the world. She had entered a new world entirely.

Her name sounded different on American tongues. Strange.

Her classmates seemed overly friendly, Anna said, one girl embracing another between classes. Odd.

Even adults were firmly taking Anna’s hand in theirs, pumping it up and down with every introduction. Weird.

“When my teacher shook hands with me,” Anna said, “I didn’t know that culture.”

What surprised Anna the most, though, wasn’t a hallway hug or a teacher’s handshake—the first of many culture shocks she would experience in the next few years.

It was that she didn’t know English.

She had prepared, she thought.

Anna studied the language for years in Japan and briefly in Oakdale Elementary’s ESL department, she said, convinced her avid study had sufficiently ingrained the 26 letters in her mind.

She knew countless English words like the back of her hand, phrases she’d memorized across years of high academic achievement.

But as any Community foreign language student fresh out of a rapid-fire listening exam could attest, high grades and quick memorization rates don’t always mean authentic comprehension.

“My knowledge when it came to English,” Anna said, “was close to zero.”

The isolation left Anna senseless that first day, tears blurring her vision as her ears, too, were rendered useless from the hours of gibberish.

“I was just sitting alone,” Anna said, “and almost cried because I couldn’t understand.”

The entire day felt like an impossibly difficult foreign language class, but there was no way out. No easy grade boost. No friend to complain to in a familiar language, as none of Anna’s peers nor ESL teachers spoke Japanese. And certainly no opportunity to ‘drop the class.’

Like countless other ESL students, the constant confusion was her reality—but she was determined to make it a temporary one.

One Chromebook tab perpetually open to Google Translate, Anna said, she did the only thing she could do: study.

She spent hours deciphering paragraphs.

Revising writing of her own.

Taking notes on her mistakes.

But ‘study’ didn’t mean pouring over written words exclusively.

It meant going on her first road trip with an American friend, learning to ask whether the animal on a passing farm was called a horse or a cow without fear of embarrassment.

It meant exploring clothing stores, learning how to do makeup and getting highlights in her freshly cut hair—the things American girls seemed to love, and that Anna was starting to love too.

It meant discovering that in America, there was more to school than school itself.

Anna might have learned more—if not academically, then culturally—in the school’s hallways than its classrooms.

It didn’t take many overheard conversations for Anna to realize: Americans cared less about academics than her Japanese peers did. In Japan, her friends were constantly asking for her test scores—focused on the metrics, essays and presentation skills that would one day earn them college acceptances.

“They didn’t have freedom,” Anna said, “because they had to study.”

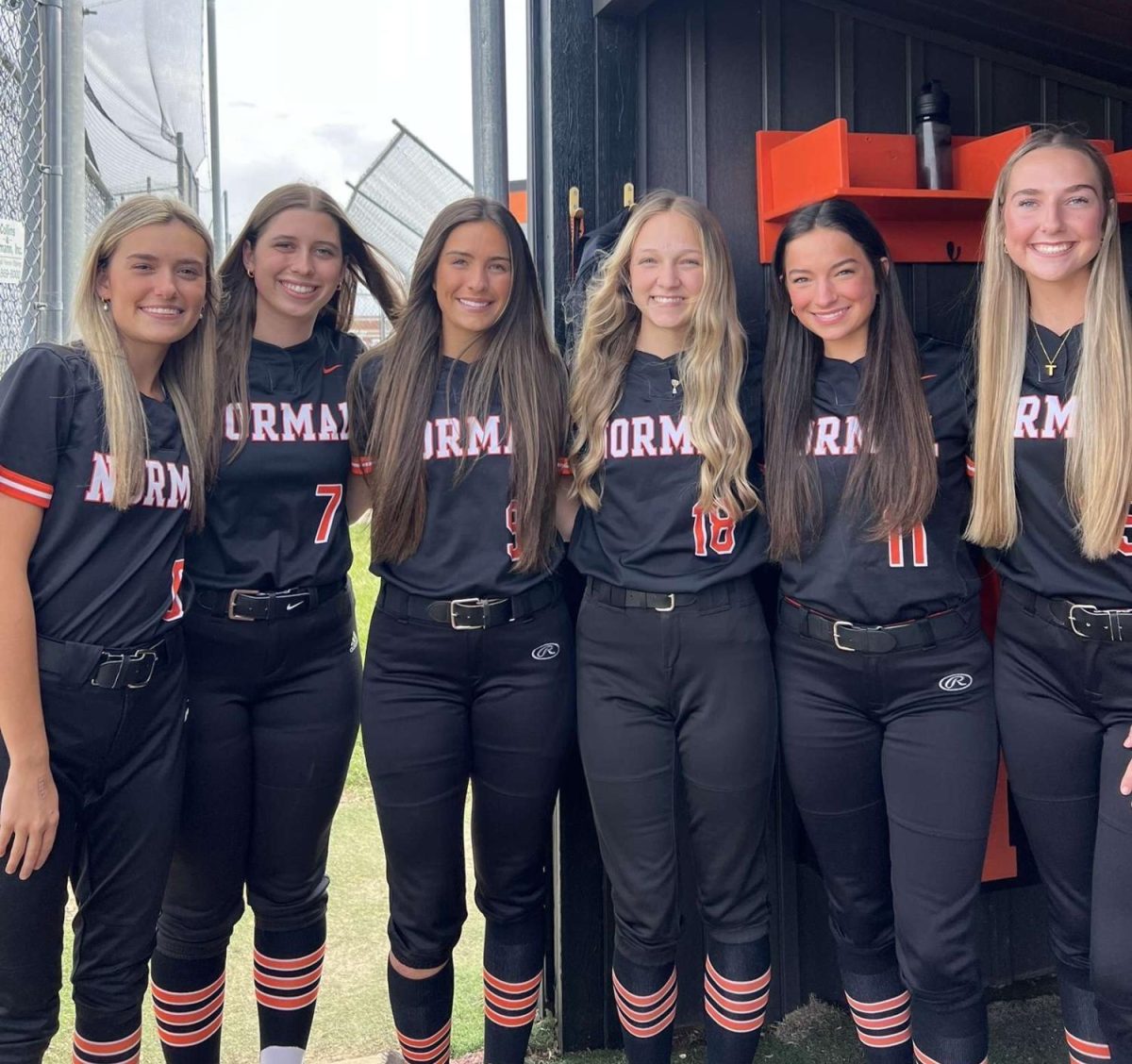

But in America, Anna said, students “see people by their school activities.” For Anna, questions about friends’ athletic accomplishments, interests and volunteer work started to replace the constant “What was your score on the test?” she heard in Japan.

Here, extracurriculars were everything.

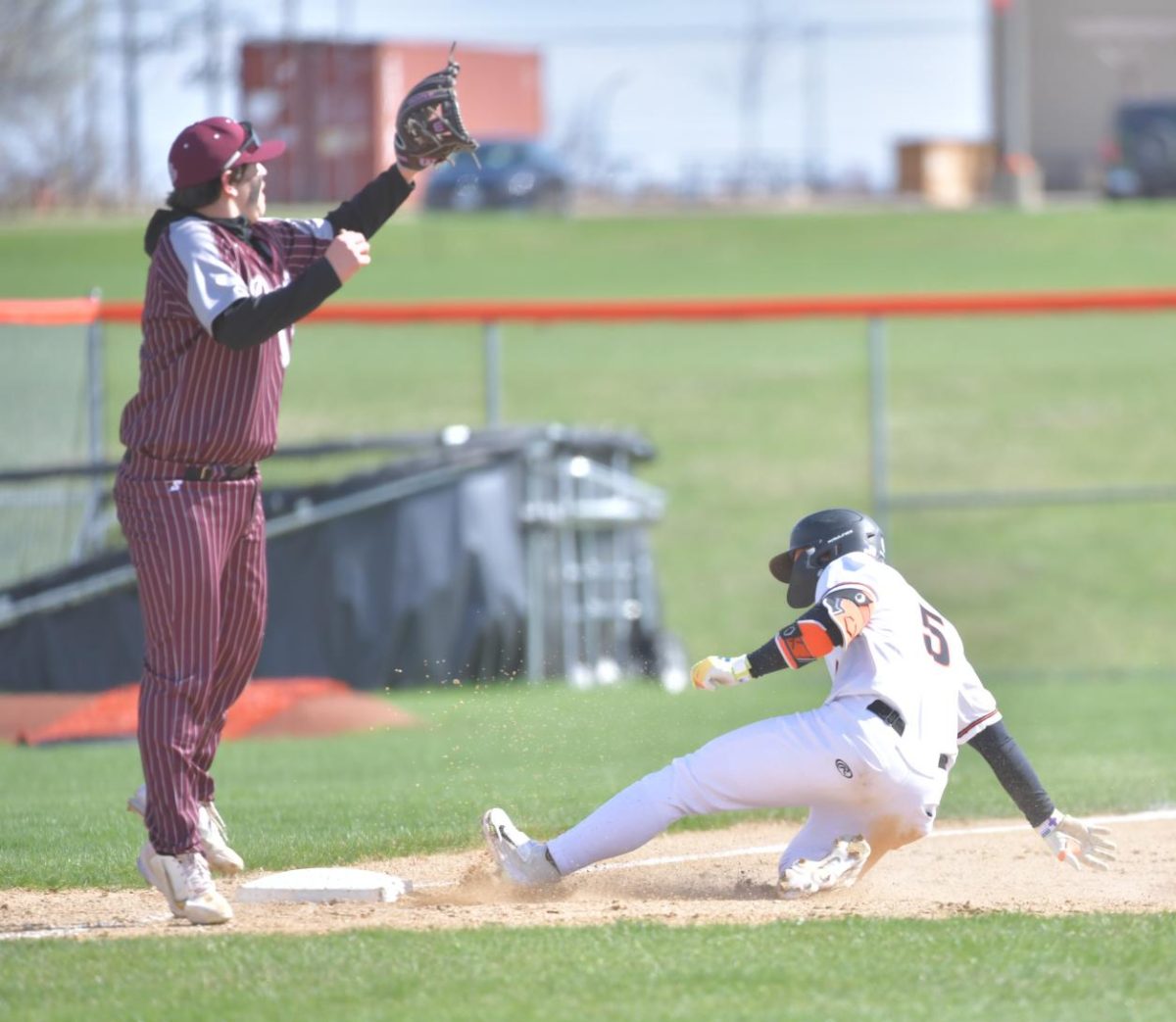

Within one spring at Chiddix, a new friend had already dragged Anna to her first track open gym on a cracked, weed-infested oval of asphalt behind the school. Just like that, Anna’s long-distance running career had begun.

Anna said she never considered herself an athlete before, never belonged to a team like what she found at Chiddix and later Community, yet here she was—running that worn-down track because, she now knew, she loved it.

Surrounded by track teammates and other friends, Anna began to absorb the ‘do what makes you happy’ sentiment and build a more confident voice.

School wasn’t teaching Anna foreign content like English or American history. It was showing her how to express what she had all along: herself.

Attending Chiddix and Community allowed Anna to break free from the uniforms, makeup bans and haircut restrictions of her Japanese school—so she could say more about who she was without speaking a word.

“The United States is freedom-based,” Anna said. “There’s so much freedom.”

Americans even speak more freely than her Japanese peers, Anna said. For ESL students, that can be the hardest part— not just learning to speak, but colloquially talk.

While Anna said her Japanese friends often tiptoe around conflict out of politeness—making social situations “weird” or “confusing”—Americans are generally less afraid to confront each other.

“If they want to say something,” Anna said, “they say it straight.”

Anna said that before coming to America, she often lacked the confidence to say what she truly meant—fearing others’ judgment or comments about her intelligence.

Now, though, she said she feels free to “challenge” people’s ideas and prioritize what she wants to communicate over what is most palatable—a lesson more valuable than any mathematical formula.

So when Anna packed her bags for the 15-hour flight back to Japan this January, she returned with more than her belongings.

After five years—COVID prolonged her family’s original stay—she returned with a clear image of how she wanted to live. And she’s already getting a taste of it in Japan.

Now a student at Nagoya International Junior and Senior High, Anna attends school alongside Japanese speakers from every corner of the world—including Illinois.

The global connection has been essential to maintaining her new English skills, Anna said, but it has been even more crucial to her confidence. Exposed to such a diverse population in America and now at Nagoya, she no longer fears being bullied for an accent among her Japanese peers—most of whom she last saw in elementary school.

“I was excited to see how they’d changed,” Anna said, “because not many Japanese people post on Instagram.”

But now that she’s lived in America, she still longs for something.

She loves Japan, but she still misses having short hair and wearing whatever she wants.

She’s still staying up until four in the morning some days, hoping to return American friends’ Snapchat messages in real time rather than replying hours late.

She’s still itching to show up at track practice, she said, missing the sport she said changed her “physically and mentally.”

And she still remembers the way she glanced out her mom’s minivan window that Illinois morning five years ago, passing periods and PE clothes feeling like the most important things in the world.

Now, as a much different scene whizzes past during Anna’s train ride to Nagoya each morning, her priorities have shifted.

Now, she’s thinking about the day she comes back.

The day she starts college in America.

The day she finally follows her dream, living in the country where her most valuable lesson wasn’t about English and had nothing to do with a locker combination.

“Coming to the U.S.,” Anna said, “taught me that being yourself is the most important.”

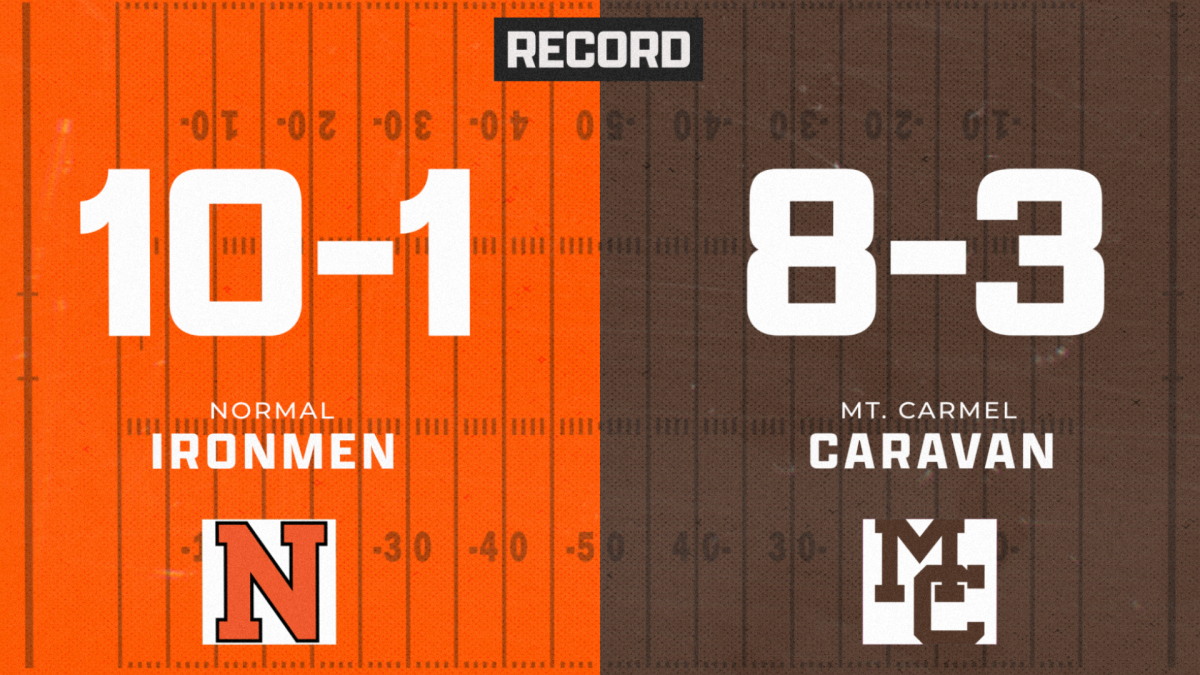

![Coach Drengwitz on the loss to Mt. Carmel, 2024 season [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Postseason-presser-feature-1200x800.png)

![IHSA 7A Football Playoffs Quarterfinals: Ironmen head coach on facing the Mt. Carmel Caravan [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/0w12-web-feature-1200x800.png)

![Halloween candy cross section quiz [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Candy-cover-big-900x675.png)

![Average Jonah? [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/average-jonah-900x600.png)

![Cell phone ban in schools? Community responds to proposed legislation [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Sequence.00_01_09_19.Still001-1200x675.png)

![Ironmen spring sports update: April 9 [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/sports-recap-square-1200x1200.png)

![Ironmen in the hunt: Coach Feeney talks Big 12 Title race ahead of PND matchup [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/feeney-1200x675.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Halloween [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/tot-Halloween-YT-1200x675.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Fall favorites [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/ots-fall-web-1200x800.png)

![On the Spot – Teachers tested on 2023’s hottest words [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/On-the-Spot-Teachers-tested-1200x675.png)