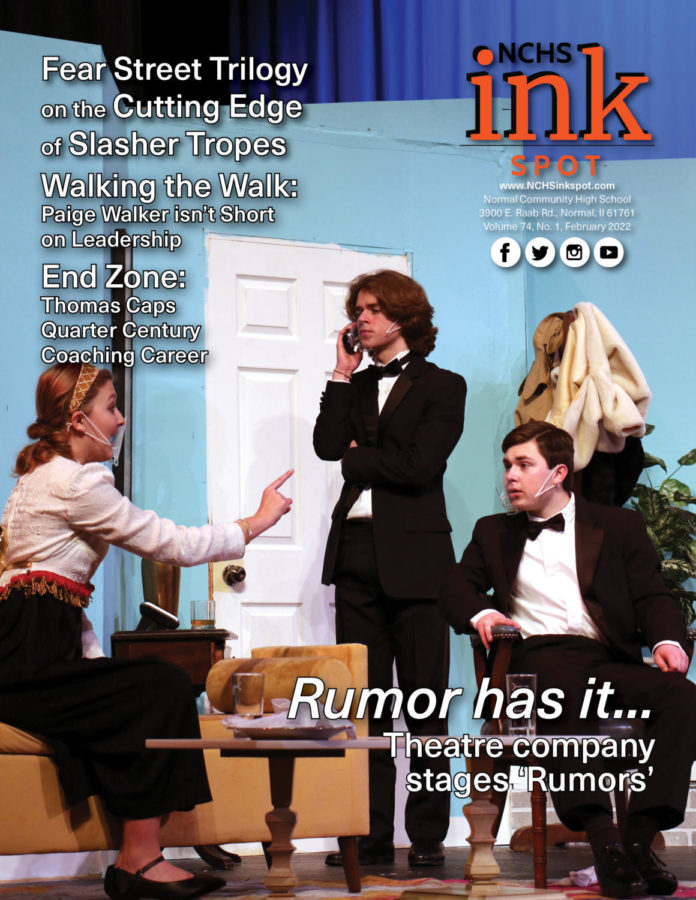

Note: this article originally appeared in the February 2022 Inkspot magazine.

A surgical dissection of horror films, peeling back their skin, reveals a genre embodied by several sub-genres: the psychological thriller— “Silence of the Lambs” (1991), “The Sixth Sense” (1999), “The Shining” (1980); paranormal found footage films—“The Blair Witch Project” (1999), “Paranormal Activity” (2007), “The Visit” (2015); the slasher…

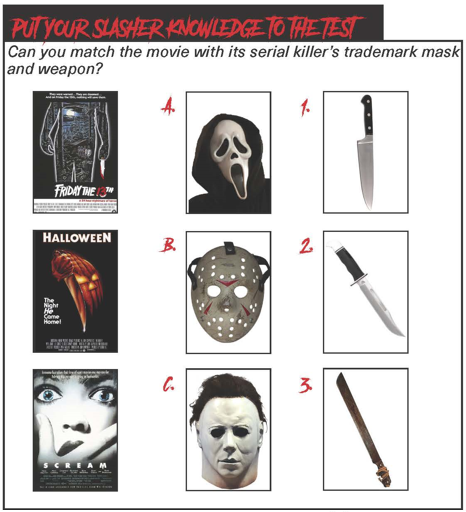

Cut into slasher film after slasher film and out spill its tropes: psychotic killers (Michael Myers, Jason Voorhees) wearing grotesque masks (hockey goaltender mask, Ghostface, and whatever Michael Myers covers his face with) equipped with razor-sharp weapons (chef’s knife, machete, hunting knife) committing gory, gruesome murders.

Cut into slasher film after slasher film and out spill its tropes: psychotic killers (Michael Myers, Jason Voorhees) wearing grotesque masks (hockey goaltender mask, Ghostface, and whatever Michael Myers covers his face with) equipped with razor-sharp weapons (chef’s knife, machete, hunting knife) committing gory, gruesome murders.

It’s a little repetitive.

While the formula can be, well, formulaic, with the masked killer and the final girl, and the gore gross—it hasn’t stopped slasher films from killing it at the box office and spawning successful franchises.

The year they were released, films like “Scream” (1996), “Halloween” (1978), and “Friday the 13th” (1980) grossed in the box office’s top 20.

Just like the killer who just won’t die, these franchises aren’t dying out either with “Scream’s” fifth installment released earlier this year, and “Halloween” released its newest film, number 12 in the series, in 2021.

These horror staples have seen success while never deviating, never detouring from their tropes.

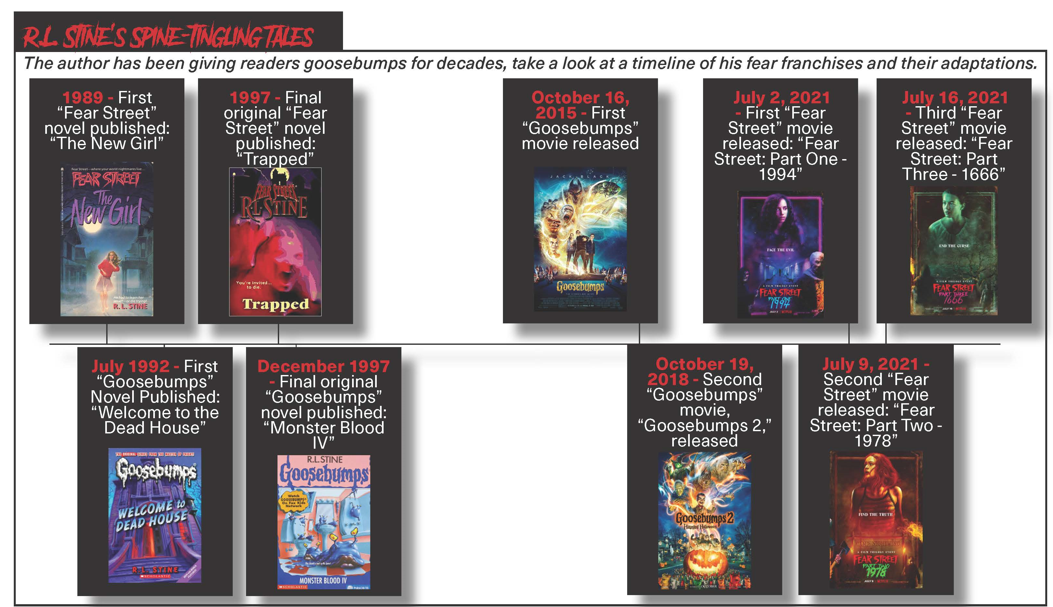

Netflix’s “Fear Street” trilogy, based on R.L. Stine’s young adult horror series, offers a break from the tropes, shifting to new ideas.

Netflix’s three-part adaptation of Stine’s source material follows a circle of teenage friends that accidentally encounter an ancient evil responsible for a series of brutal murders that have plagued their town for over 300 years.

Director Leigh Janiak’s trilogy takes popular slasher and horror tropes and eviscerates them.

Janiak (“Honeymoon”) redefines the slasher sub-genre by challenging horror’s “Bury Your Gays” trope—where LGBTQ characters are expendable—killed off, early and often, or portrayed as the villain.

This reductive portrayal of LGBTQ characters reappears again and again in the horror genre as a whole—rearing its ugly head in media like “Jennifer’s Body” (2009), “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” (1997), and “American Horror Story” (2011).

Janiak’s trilogy introduces audiences to a rare portrayal of the resilient queer protagonist in mass-released horror. Her queer characters are not stereotypes or stock characters to be stabbed and slashed, but the heroines at the heart of the films.

The Fear Street trilogy depicts queer characters and a queer relationship that feels fleshed out and real. The two main characters, Deena Johnson (Kiana Madeira) and Samantha “Sam” Fraser (Olivia Scott Welch), both face their share of hardships (Sam’s sexuality and Deena’s absent father) throughout the three films. Both Deena and Sam have to address their own problems while also trying to save Shadyside from an endless cycle of peril and their relationship.

Janiak, in an interview with film critic Kristy Puchko, said that it was not easy for Sam to come out in the film and wanted to keep the relationship true to the experience of being queer in the 90s.

“We wanted to preserve that and make sure that we were telling a specific story,” Janiak said, “not just a straight story that happened to have two women in it.”

The queer protagonists in the trilogy are essential to the build-up of the central conflict within the series—characters being depicted as villains because of their sexuality.

While the audience believes that Sarah Fier (known as the witch who cursed Shadyside) is the trilogy’s main villain, the third installment shows that Fier was an innocent girl in a homosexual relationship in 1666. Fier is a scapegoat for the real antagonist of the story, Solomon Goode, and is vilified for her sexuality.

In the third installment, “Fear Street: Part Three – 1666”, Sarah Fier’s community torments and publicly hangs her for being gay. Although the scene is blatantly homophobic and it depicts the “Bury Your Gays” trope, those choices were purposeful for Janiak, setting up the central conflict the protagonists have to solve.

“I’m obsessed with this idea of the mistakes of history and cycles of time,” Janiak said, “which I think is clear in the movies.”

Setting with the second and third installment in the past, 1978 and 1666, allows Janiak to comment on society through the repetition of the cycle that is set up in the first films 1994 timeline.

“We show what happened in 1666 with Sarah and Hannah and how that world certainly was not ready for them,” Janiak said.

Breaking the cycle of victimization, Deena and Sam show that they are ready to rewrite history, both with their relationship and the Shadyside curse.

Besides challenging the “Bury Your Gays” trope, “Fear Street” diverts from typical slasher path where teenagers are the victims, with the trope of the final girl surviving because she maintained her virginity, her innocence (again an example of the horror genre vilifying sexuality.)

This depiction of purity extends to children in the horror world. Where children survive the stabbings and slashes because of their innocence —creating the slasher’s “Wouldn’t Hurt a Child” trope. The trope’s seen in movies like “Friday the 13th Part VI: Jason Lives” (1986), when Jason Voorhees spares children during his rampages.

Janiak instead uses her murderous characters to brutally kill and mutilate everyone in their path, including the children.

In “Fear Street: Part Two – 1978”, the typical slasher summer camp setting sets up the obvious and overdone: teens getting severed by the murderer. While plenty of teenagers are slaughtered during the second installment, no one is safe, not even the children.

The mass murderer of the second film, The Nightwing Killer, aka Tommy Slater (McCabe Slye), lacks even the basic morality that often stops the cinematic serial killer from cutting up kids.

During the camp counselor’s carnage, the audience watches Tommy corner a cabin full of young campers, creating havoc, and bringing his axe upon them. He also shows no remorse for the children as he swings his axe and butchers the nerdy kid he had developed a relationship with earlier in the film.

The adolescent annihilation present in the second film carries over into the third installment, “Fear Street: Part Three – 1666.”

In 1666, ‘The Pastor’ Cyrus Miller (Michael Chandler) corals children in the community and lures them into the church, where they meet their murderous demise. In turn, wiping out all the children in the settlement and the “Wouldn’t Hurt a Child” trope. In one scene, Janiak critiques societal views on the relationship between sexuality and innocence and condemns institutions with histories of abusing children.

The “Fear Street” trilogy shifts from the tropes and techniques of traditional slasher films and defies the use of toxic and redundant tropes. The “Fear Street” franchise deviates from what slasher franchises adhere to, creating a unique three-part series that gives a refreshing take on the tropes.

With loose ends untied and a cliff-hanger at the end of the third installment, there is room for the series to continue—and good reason for it to.

Janiak hopes to continue the films with the rich and abundant source material to carve into.

“One of my earliest conversations when I first started coming aboard,” the director said, “was describing the potential of this [franchise]. The way I saw it was as Horror Marvel.”

![Community honors longtime coach Mr. Bryan Thomas before Oct. 3 game [photo gallery]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Thomas-6-1200x1200.jpg)

![Week 7: Coach Drengwitz recaps the Ironmen’s win over Bloomington, talks Danville [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Vikings-feature-Image-1200x675.png)

![Halloween candy cross section quiz [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Candy-cover-big-900x675.png)

![Average Jonah? [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/average-jonah-900x600.png)

![[Photo Illustration]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/trigger-words.png)

![Week 5: Coach Drengwitz previews the Ironmen’s matchup vs. Peoria Manual, recaps Week 4 [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Week-5-v-Rams-1200x675.png)

![Postgame reaction: Coach Drengwitz on Community’s 28-17 Loss to Kankakee [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Week-4-postgame--1200x675.png)

![Week 4: Coach Drengwitz previews the Ironmen’s matchup vs. Kankakee [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ironmen-v-Kankakee-video-1200x1200.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Halloween [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/tot-Halloween-YT-1200x675.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Fall favorites [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/ots-fall-web-1200x800.png)

![On the Spot – Teachers tested on 2023’s hottest words [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/On-the-Spot-Teachers-tested-1200x675.png)