Vampires used to skulk in crumbling castles, draped in capes and centuries-old rot. Now they wear pressed suits, flash charming smiles—and drain entire cultures dry.

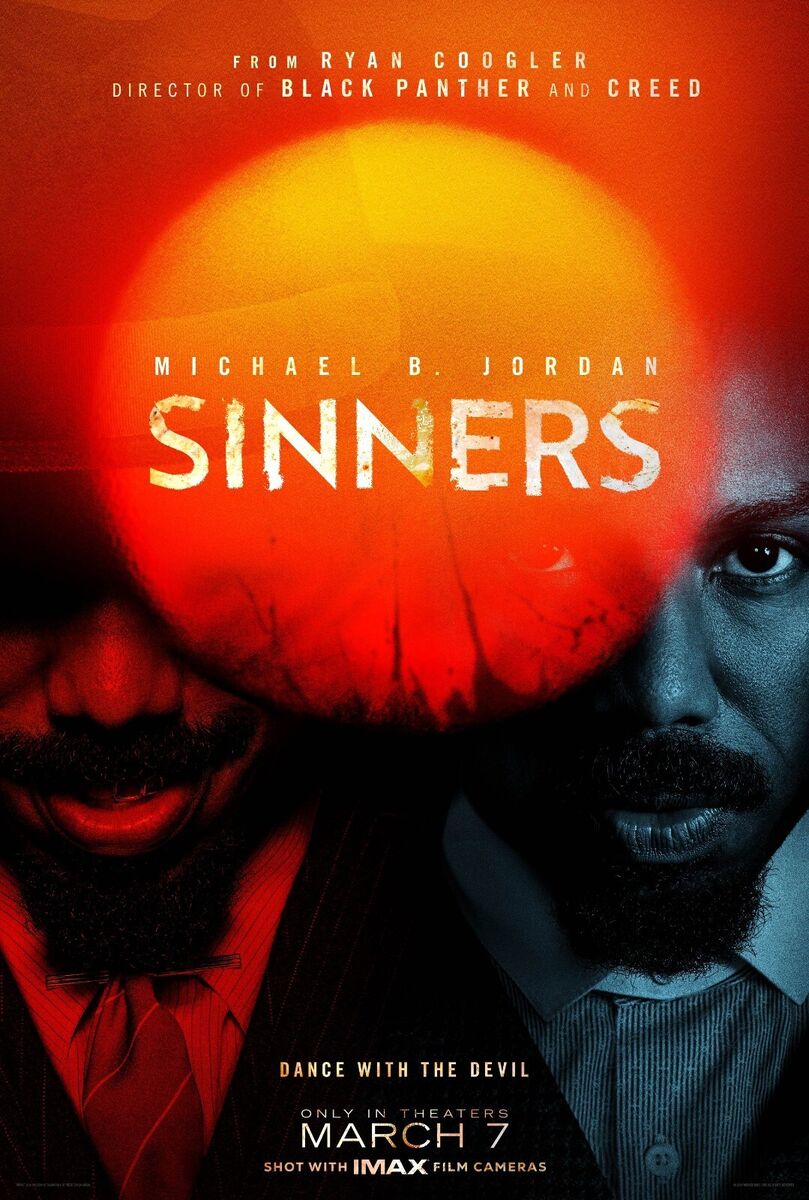

With “Sinners,” director Ryan Coogler trades jump scares for generational trauma. His fifth feature, following “Creed” and the “Black Panther” films, is less about fangs and more about what’s been stolen: heritage, music, identity. The horror here isn’t the undead—it’s the allure of assimilation.

Coogler has long centered his work on Black resilience and reinvention. In “Sinners,” he pushes further, framing cultural theft as vampirism: a parasitic force that seduces, then consumes.

It’s no coincidence this project follows Coogler’s own brush with misidentification—in 2022, he was wrongfully arrested while trying to make a withdrawal from his own bank account.

That incident echoes throughout “Sinners,” a film about who gets to own history and who gets mistaken for a threat.

Set in 1930s Mississippi, the film follows Sammie (Miles Caton in his debut role), a gifted musician caught between sacred tradition and secular ambition. Against his father’s wishes, Sammie joins his cousins—twin brothers Smoke and Stack—in opening Club Juke, a juke joint pulsing with promise and peril.

Michael B. Jordan plays both twins with swagger and subtlety: Smoke, stoic and protective; Stack, slick and self-serving. It’s a dual performance that doesn’t feel like a gimmick—it feels like a myth.

Jordan vanishes into each role so completely that you forget you’re watching the same actor. He plays each with such distinct physicality and rhythm that it’s less like watching an actor play twins and more like watching a legend unfold in real time. He fully embodies both archetypes, split reflections of survival under pressure—one trying to shield what’s his, the other trying to hoard what he can. Even the character names nod toward the film’s theme of consumption: Smoke, what’s left after the burning, and Stack, what’s accumulated in its wake. They echo the industrial hunger that powers vampirism in the film—a cycle of taking, draining, and leaving behind.

Despite what the trailers suggest, “Sinners” is no action-first bloodbath. The film simmers, letting its human characters breathe before its inhuman ones arrive. The first half plays like a blues riff—loose, lively, deceptively simple. Townsfolk drift in and out of Club Juke, each encounter revealing a wound: a pastor struggling with his son’s drift from faith, a woman nursing heartbreak, a drunk masking a lynching he witnessed. Their pain lingers like smoke in the air—a breath never fully exhaled.

When the vampires show up, they don’t kick down the door. They wait for an invitation. They flatter. They flirt. They talk about God and goodness and “shared history.” Like colonizers, they mask their hunger in hospitality.

The real horror of “Sinners” isn’t the vampire’s bite—it’s the conversation before it. Coogler’s vampires don’t pounce; they persuade. They whisper like old friends, invoke memories only lovers would know, threaten children without raising their voices. Whether you rush outside to save someone or scream for the bloodsucker to come in and fight, the result is the same: you’ve surrendered your will. The seduction isn’t supernatural—it’s psychological.

And that’s what makes it terrifying. You don’t just believe the lie. You invite it in.

Chief among the predators is Remmick, a charismatic Irish vampire with a choir boy’s voice and a colonizer’s thirst. Played with icy charm by Domhnall Gleeson, Remmick isn’t after blood—he’s after Sammie’s song. Because in this world, Sammie’s music doesn’t just move people. It connects them to ancestral memory. His playing conjures the past—pulling generations into the present, a spiritual counterpunch to the vampire’s hive-mind conformity.

In a stunning midpoint sequence, Coogler contrasts two visions of community. First, Sammie’s music summons a chorus of past lives—musicians across eras and cultures joining in celebration. Then, Remmick answers with his own melody: a mournful Irish ballad steeped in historical pain. He, too, has a colonized past. He, too, lost language, land and legacy. But unlike Sammie, he responds by turning others into him. His dream isn’t communion—it’s consumption.

This is where “Sinners” bares its fangs. The metaphor clicks. Vampirism becomes more than horror—it’s the death of individuality. The seductive danger isn’t just in being bitten. It’s in being convinced the bite is a blessing.

Coogler plays the horror for both laughs and dread. Some of the film’s funniest scenes come when the vampires try to gaslight their way inside: “Just let us in for a drink,” they purr, while their eyes glow and fangs peek through.

But even as the audience laughs, the tension never breaks. Because all it takes is one slip of the tongue, one accidental invitation and the party becomes a feast.

The film’s production crackles with intention. The score, like the story, bridges cultures—soulful blues tracks trade licks with eerie synth and haunting jigs. The cinematography embraces contrast: warm amber tones inside Club Juke, cold blues whenever the vampires lurk near. And in IMAX, Coogler’s use of shifting aspect ratios turns musical numbers into spiritual awakenings and action scenes into opera.

That said, not everything lands. A few characters feel shielded by plot armor, and some thematic beats are a little too on the nose. But these are small stumbles in an otherwise electric film.

“Sinners” is the rare genre movie that manages to entertain, provoke and haunt. Like its vampires, “Sinners” is seductive. But unlike them, it gives more than it takes.

![Community honors longtime coach Mr. Bryan Thomas before Oct. 3 game [photo gallery]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Thomas-6-1200x1200.jpg)

![Ironmen volleball head coach Ms. Christine Konopasek recorded her 400th career victory Oct. 21 as the Ironmen closed their regular season with a 2-0 sweep over Danville.

[Photo Illustration]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Vball400Thumb.png)

![Halloween candy cross section quiz [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Candy-cover-big-900x675.png)

![Average Jonah? [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/average-jonah-900x600.png)

![[Photo Illustration]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/trigger-words-1.png)

![Week 9: Coach Drengwitz on Week 8’s win, previewing Peoria High [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/W9_PeoriaThumb.png)

![Postgame: Drengwitz on Community’s 56-6 win over Champaign Centennial; staying unbeaten in Big 12 [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/10.17_FBwChampCent56-6_POST_thumb.png)

![Week 7: Coach Drengwitz recaps the Ironmen’s win over Bloomington, talks Danville [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Vikings-feature-Image-1200x675.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Halloween [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/tot-Halloween-YT-1200x675.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Fall favorites [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/ots-fall-web-1200x800.png)

![On the Spot – Teachers tested on 2023’s hottest words [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/On-the-Spot-Teachers-tested-1200x675.png)