Top 5 Studio Ghibli films

I didn’t grow up with Ghibli films like a lot of the studio’s fans—a casualty of my parents’ “quality control,” turning off anything they deemed “stupid.” Anything animated, like “Adventure Time” or “Regular Show,” automatically fell into this category.

And as a result, I never experienced the rich worlds that animation legends Hayao Miyazaki or Isso Takahata crafted through the lens of a child. I never witnessed the beauty of “Spirited Away,” the fun of “Ponyo” or the emotions of “When Marnie was There” from that perspective.

It’s only been a few years since I could turn on the TV without fearing my parents would turn off what I wanted to watch in disapproval. I watched my first Ghibli around this time last year, through the eyes of a teenager. Eyes that find it a little harder to see wonder in the world.

I’ve worked my way pretty far through the catalogue in the meantime.

While the films lack a sense of nostalgia for me, discovering the studio’s films when I did, at 16, was still nothing short of revelatory.

Ghibli’s films bridge the gap between childhood wonder and profound life lessons, delivering timeless messages about self-discovery and human connection, critiquing the faults of society on a scale both grand and small.

Studio Ghibli is more than an animation studio; it’s a master of storytelling that transcends age and culture.

With Ghibli nearing its 40th anniversary and several iconic films marking milestone anniversaries, there’s no better time to rank the five best films. These films are the beating heart of Ghibli’s legacy, each a gem that continues to inspire audiences worldwide.

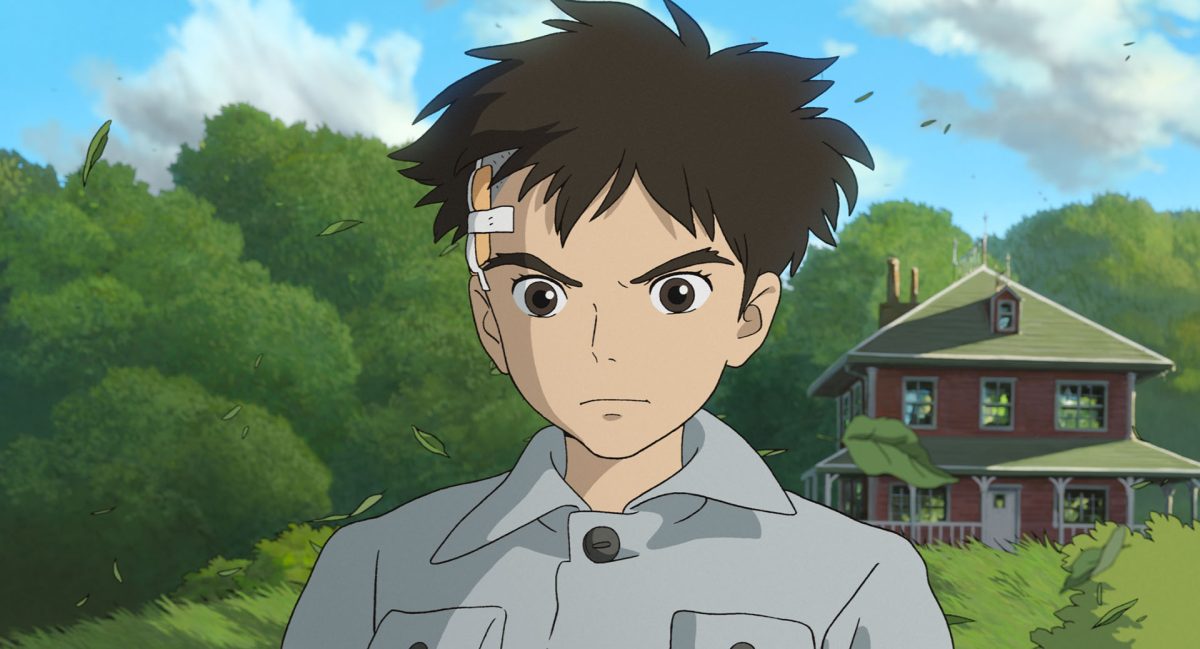

Ghibli’s latest release is a triumph of breathtaking artistry and personal storytelling. In one word: it’s beautiful.

Every frame pulses with vibrant colors and stunningly intricate designs, from the teeming wildlife to the rich, expressive environments. This isn’t just eye candy—each visual element deepens the narrative, drawing the viewer into a story steeped in grief and self-discovery. This is a world that lives and breathes, it is authentic.

Inspired by Hayao Miyazaki’s own life, “The Boy and the Heron” follows Mahito, a boy grappling with loss after his mother’s death during World War II. Mahito’s move to his late mother’s countryside home, one inhabited by her lookalike sister, mirrors Miyazaki’s own childhood, infusing the film with an added layer of authenticity and emotional weight.

Mahito’s journey throughout the film is about learning to accept his new life, learning that although things are different, he doesn’t have to be consumed by his grief.

While his mother can never be replaced, Mahito realizes that he’s capable of building more familial relationships.

On another level, “The Boy and the Heron” reflects Miyazaki’s thoughts on legacy.

Following his initial retirement after “The Wind Rises” (2013), there was widespread speculation about the studio’s future. Fans hoped for another “Miyazaki,” a successor to carry the torch. A lookalike sister to replace the mother.

The failure of “Earwig and the Witch” (2021), directed by Miyazaki’s son, Goro, underscored the impossibility of the son truly replacing his father.

This film pushes back against that expectation, championing the idea that every creator must chart their own path. “The Boy and the Heron” is a farewell and a rallying cry, reminding us that while Miyazaki’s era may one day end, Ghibli’s influence will inspire countless unique voices.

The film does what Ghibli does best–using the genre of animation to explore the three dimensional depths of the human experience: grief and acceptance; individuality and family. It is dark and hopeful. Tragic and optimistic. Its everything a Ghibli film should be.

Contrary to what the film’s promotional art would have you believe, “Whisper of the Heart,” is one of the studio’s most grounded films. Absent are the fantastical and magical elements that are trademarks of the studio’s other works, focusing instead on the quiet struggles of adolescence.

The result is what I believe to be the greatest coming-of-age film, a perfect encapsulation of the struggle to find purpose and passion in life.

Shizuku, a middle schooler adrift in the monotony of schoolwork, dreams of something more. Yet, those dreams are incomplete. Life feels purposeless, she is directionless.

Shizuku’s disinterested in academic success, despite everyone around her stressing the importance of studying, getting good grades and making it into a good high school.

It is her yearning for creative fulfillment that makes her one of Ghibli’s most relatable protagonists. She’d rather read than study, rather write a piece of music for the choir than earn an A on an exam. Interests those around her can’t understand.

The story’s heart lies in Shizuku’s relationships.

Seiji, her love interest (as much as a middle-schooler can have one), is a violin craftsman with dreams of studying in Italy. His unrelenting passion ignites her own, inspiring her to write a novel that proves her dedication to storytelling.

Their romance is charming and believable, evolving naturally as the two find mutual encouragement and understanding. Just as touching is Shizuku’s bond with Seiji’s grandfather, whose bittersweet story of lost love and a cherished statue spurs her first creative spark.

“Whisper of the Heart” captures the often-overlooked tensions of growing up—balancing the pursuit of passion and development with the need to embrace the fleeting nature of childhood. One should want to grow up while still making the most out of their childhood. You can’t rush growth, the film argues.

It celebrates the idea that you should cultivate your passions, yet not abandon every other responsibility in their pursuit. That passion can become obsession, and there the joy can be lost.

Over the course of the film, Shizuku learns that growth is gradual, that it’s okay to stumble along the way. The film’s most memorable moment comes when Seiji’s grandfather critiques Shizuku’s first draft, acknowledging its flaws but praising her effort.

His advice—“You have to find the rough gems inside yourself, take the time and polish them”—speaks to anyone who has ever struggled with self-doubt.

The man, and the film, argues that despite the work’s flaws, the effort put in wasn’t for nothing. Each piece is a step closer to the perfection you strive for. Each step is a chance to improve. Mistakes are only mistakes if you refuse to learn from them.

The film’s ability to connect deeply with its audience, through both its story and its characters, solidifies its place among Ghibli’s best.

It’s an ugly fact of life, a universal truth, that we all experience some sense of being uncomfortable in our own skin, in one way or another. In a world obsessed with beauty standards, few films capture the complexities of self-image and insecurity as beautifully as “Howl’s Moving Castle.” The film is a resonant critique of self-image and superficiality colored in the Ghibli pallet.

Sophie, the film’s protagonist, has never felt beautiful. That insecurity is magnified through a curse, with each thought of self-doubt Sophie transforms a little more into an old woman.

The curse is a metaphor–her ugly thoughts of self-criticism manifesting in, what she believes is, literal ugliness. With positive thoughts, with confidence, the process reverses. The film comments not only on the cyclical nature of negative thought–the more you think it, the more you believe it; how perception becomes reality–while celebrating the power of positive self-image as well. As Sophie ventures to break the curse, her physical transformation becomes a metaphor for embracing her identity and finding beauty within herself.

A foil to Sophie is Howl, a flamboyant wizard whose obsession with physical perfection highlights the dangers of vanity. The fact the character is voiced by Christian Bale only serves to reinforce that Howl is the embodiment of masculine beauty and charm.

His melodramatic breakdown, literally melting away, after accidentally dyeing his hair is both humorous and tragic, illustrating how superficial concerns can spiral out of control.

Howl’s emotional immaturity and escapism initially define him, but his growth—fueled by Sophie’s influence—becomes one of the film’s most compelling arcs.

Neither Sophie nor Howl are capable of making their journeys towards self-acceptance without each other. Sophie doesn’t ignore Howl’s instability. Howl is the first person to see beauty in Sophie. They love each other for who each truly is. And through each other, learn to love themselves.

It is a heartwarming romance–I refuse to believe that anyone can witness Howl gift Sophie a stunning field of flowers, as “Merry-Go-Round of Life” plays in the background and not feel moved.

Adding to the layers of the film is its exploration of war and its devastating impact on families. War, a common theme in Ghibli works, it is argued is the result of glorified pissing contests, the result of ego and vanity.

Another enriching layer, the concept of a found family that forms within the moving castle—a hatter, a magician, a boy, a scarecrow and a fire demon—is as heartwarming as it is eclectic.

How “Howl’s Moving Castle” manages to juggle romance, war, self-discovery, found family and so many other intricate themes, weaving them all seamlessly together is indicative of what makes Studio Ghibli Studio Ghibli.

And it’s why it deserves to be forever recognized as one of Ghibli’s most impressive works.

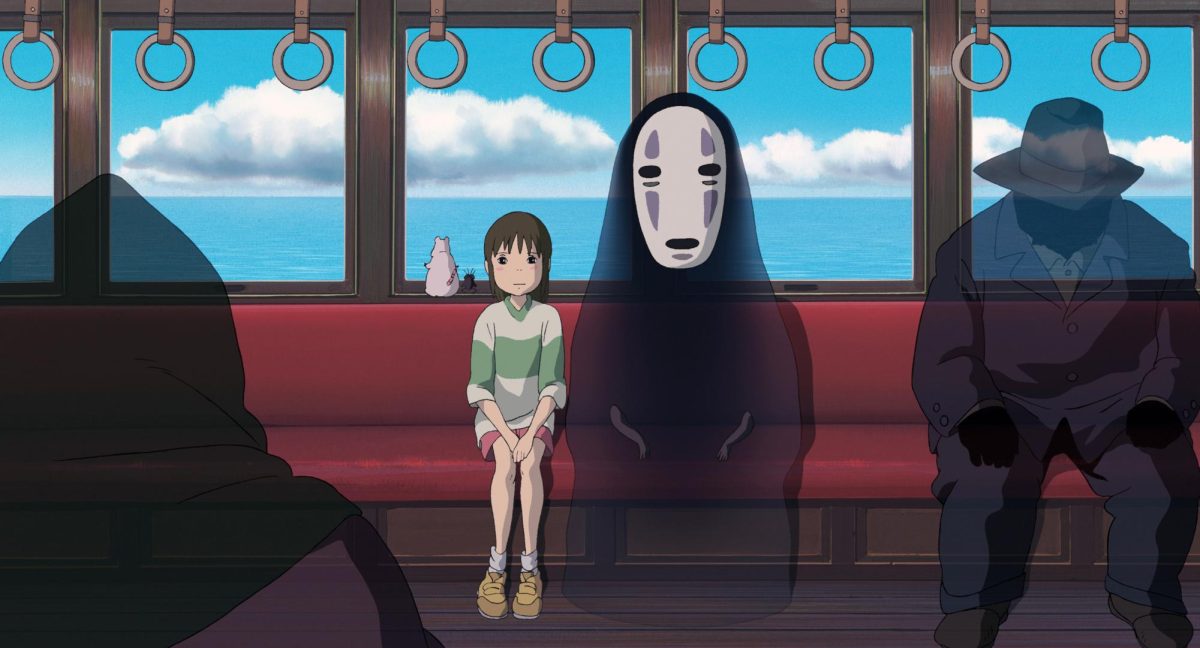

If there’s a movie that proves animation can be as deep and complex as any other art form, it’s “Spirited Away.”

This film isn’t just a towering achievement for Studio Ghibli—it’s a towering achievement for cinema as a whole. Winning the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature (only the second time it was awarded) feels like the bare minimum of recognition for something this creative, this layered and this stunningly executed.

The world of “Spirited Away” is built around the Aburaya bathhouse, a bustling and chaotic hub for spirits that’s as beautiful as it is bizarre.

Every corner of this setting is packed with detail, immersing you so deeply in its atmosphere that it feels like a place you could visit.

Every character is unforgettable, from Kamaji, the gruff but endearing boiler room operator, to No Face, whose enigmatic presence keeps you hooked. Even without speaking much—or at all—these characters’ personalities shine through in their designs, movements and interactions.

But “Spirited Away” is more than just a visual feast. It’s a sharp critique of greed, capitalism and the toll they take on humanity.

The bathhouse isn’t just a setting; it’s a symbol. Everything here runs on profit, and the costs—identity, morality and even humanity—are steep.

The workers are bound to Yubaba, the bathhouse’s ruthless and manipulative owner, by contracts that strip them of their names and lock them into servitude. She’s the embodiment of every greedy, exploitative boss, running a system that grinds people down for her benefit.

Chihiro, the film’s ten-year-old protagonist, stands as the antithesis to this system. While her parents fall victim to their own greed (literally turning into pigs after gorging on stolen food), and the bathhouse workers blindly chase No Face’s gold despite the chaos he brings, Chihiro refuses to be consumed by the world around her.

Her strength lies in her kindness, her courage and her unwavering sense of self. These qualities allow her not only to reclaim her own identity but to help others, including No Face, find redemption.

No Face is one of Ghibli’s most fascinating creations—a spirit who starts out harmless but becomes twisted by his environment. His ability to turn dirt into gold initially seems like a gift, but it quickly corrupts him.

He uses this “gold” to buy loyalty and consume those around him, stealing their voices and identities in the process. No Face is the perfect metaphor for how greed, and the systems that enable it, can distort even the most innocent.

Yet Chihiro’s kindness provides him with a way out, helping him escape the bathhouse’s toxicity and rediscover peace.

The environmental themes of “Spirited Away” are just as powerful, especially in one of the film’s most iconic moments: Chihiro’s encounter with the Stink Spirit.

Everyone avoids the foul, sludge-covered creature, dismissing it as a nuisance. But Chihiro takes on the challenge of cleaning it, only to reveal its true identity—a polluted River Spirit, burdened by humanity’s neglect and garbage.

The scene is a powerful metaphor for how younger generations are often left to clean up the messes created by their predecessors, both literally and figuratively.

Despite its heavy themes, “Spirited Away” never feels preachy. It’s a film of contrasts—joyful yet melancholic, whimsical yet deeply serious. The humor balances the darker moments and the simple humanity of Chihiro keeps the story grounded.

The world-building is unparalleled, creating a setting that’s as immersive as it is meaningful. You feel like you’re wandering through the bathhouse alongside Chihiro, discovering its secrets in real time.

At its core, “Spirited Away” is about identity, resilience and the power of compassion.

Chihiro’s journey is a reminder that even in overwhelming circumstances, small acts of kindness can ripple outward, changing everything. The film’s themes remain as relevant today as they were when it premiered, and its visual beauty is timeless.

It’s not just a masterpiece of animation—it’s a masterpiece.

“Princess Mononoke” is not only my favorite Studio Ghibli film—it’s my favorite film, period.

It takes everything that makes Ghibli amazing—jaw-dropping visuals, layered storytelling and characters who feel more real than people you actually know—and cranks it up to eleven.

From the first scene to the last, this movie hits hard, and it doesn’t let go. You feel it in your chest long after the credits roll.

The story throws you into a world where humanity and nature are locked in a violent, no-holds-barred clash.

It’s ambitious, intense and the kind of deep that makes you rethink what animation can do.

Honestly, it’s proof that my parents were way off base when they dismissed cartoons as “kid stuff.” This film doesn’t just hint at maturity—it demands it.

Like many Ghibli films, “Princess Mononoke” is populated with magical creatures and stunning landscapes. But this isn’t the warm, whimsical fantasy you might expect. The magic here has teeth—literally.

The violence is brutal and unflinching, with dismemberment, gore and outright decapitations. Every bit of it earns the PG-13 rating. But unlike some movies, the violence isn’t just there to shock. It’s purposeful, emphasizing the stakes of a world on the brink.

The plot centers on Ashitaka, a prince cursed by a demon boar after it attacks his village. The curse, marked by a festering wound on his arm, gives him superhuman strength but slowly eats away at him.

Banished from his home, he sets out to uncover the cause of the demon’s rage and to find a way to “see with eyes unclouded by hate.” His journey brings him to a forest at war—a battlefield where humanity and nature fight for survival.

On one side, there’s Iron Town, a fortress-like settlement led by Lady Eboshi, who’s ambitious, brilliant and fiercely protective of her people.

Iron Town is home to society’s outcasts—lepers, former sex workers and others the world has thrown away.

Eboshi has built a refuge for them, giving them safety and purpose. But her vision of progress requires resources, and to get them, she’s cutting down the surrounding forest, angering the spirits and gods that live there.

On the other side are the animal gods and San, a fierce warrior raised by wolves who embodies the forest’s rage. Known as Princess Mononoke, she sees humanity as nothing but destruction and has no interest in finding common ground.

Her hatred for Iron Town—and for humans as a whole—fuels her every action. She’s raw and relentless, but beneath the ferocity, there’s a vulnerability that makes her one of Ghibli’s most unforgettable characters.

What makes “Princess Mononoke” different from other films is that it doesn’t pick a side. There are no villains here. Iron Town’s destruction of the forest is tragic and horrifying, but Eboshi’s motives are rooted in compassion for her people.

At the same time, the forest’s fight to protect itself is noble but also savage, driven by rage and desperation.

Ashitaka stands in the middle, trying to mediate and bring understanding to both sides. His determination to find peace, even as both sides hurt him, makes him one of Ghibli’s most admirable heroes.

The film’s environmental themes hit hard. The forest isn’t just a backdrop; it’s alive—home to spirits and gods that symbolize the beauty and fragility of nature.

Every inch of it feels sacred, from the glowing Kodama spirits to the massive, ancient trees. When the boar gods are killed or the Forest Spirit is corrupted, it’s heartbreaking. These moments show the devastating cost of prioritizing progress over balance. The Forest Spirit, a towering figure that embodies both life and death, is one of the most powerful symbols in the movie. Its death at the hands of Iron Town’s forces is gut-wrenching, but its rebirth in the final moments suggests that renewal is possible—if humanity is willing to change.

Really, though, the characters are what make this movie unforgettable. Ashitaka’s quiet strength and unwavering selflessness make him the perfect mediator. San’s raw emotion and fierce loyalty to the forest give the story its heart. And Lady Eboshi? She’s one of the best antagonists in all of film. She’s not evil—she’s a visionary whose actions, while destructive, are born from a genuine desire to help the marginalized. Her complexity ensures that the conflict feels real, with no easy answers.

Visually, “Princess Mononoke” is next-level.

The forest teems with life, from the smallest insects to the massive wolf and boar gods. The animation in the battle scenes is so precise and intense that you feel every blow.

Even the quieter moments, like Ashitaka’s interactions with the Kodama or his first meeting with San, are visually stunning. The way the film balances beauty and brutality, light and dark, is unmatched.

At its core, “Princess Mononoke” is about balance—between humanity and nature, progress and preservation, hatred and understanding.

It’s a story that feels just as relevant now as it did when it was released. With its stunning visuals, complex characters, and powerful themes, this film isn’t just a masterpiece—it’s proof of what storytelling can achieve.

If you value the Inkspot’s commitment to student journalism—giving Normal Community’s reporters real-world experience—please consider donating to support our staff’s trip to the National High School Journalism Convention.

Your generosity helps us cover travel costs, enter national contests and attend sessions led by top media professionals—an unforgettable opportunity to learn, grow, and represent Community on a national stage.

THANK YOU for investing in the next generation of storytellers.

![Community honors longtime coach Mr. Bryan Thomas before Oct. 3 game [photo gallery]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Thomas-6-1200x1200.jpg)

![Ironmen volleball head coach Ms. Christine Konopasek recorded her 400th career victory Oct. 21 as the Ironmen closed their regular season with a 2-0 sweep over Danville.

[Photo Illustration]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Vball400Thumb.png)

![Halloween candy cross section quiz [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Candy-cover-big-900x675.png)

![Average Jonah? [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/average-jonah-900x600.png)

![[Photo Illustration]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/trigger-words-1.png)

![Week 9: Coach Drengwitz on Week 8’s win, previewing Peoria High [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/W9_PeoriaThumb.png)

![Postgame: Drengwitz on Community’s 56-6 win over Champaign Centennial; staying unbeaten in Big 12 [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/10.17_FBwChampCent56-6_POST_thumb.png)

![Week 7: Coach Drengwitz recaps the Ironmen’s win over Bloomington, talks Danville [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Vikings-feature-Image-1200x675.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Halloween [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/tot-Halloween-YT-1200x675.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Fall favorites [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/ots-fall-web-1200x800.png)

![On the Spot – Teachers tested on 2023’s hottest words [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/On-the-Spot-Teachers-tested-1200x675.png)