Firefighter, lawyer, flight attendant.

When Mattel’s Barbie hit the shelves in 1959 as an unrealistically tiny-waisted blonde in a designer bathing suit, it was impossible to predict the countless occupations the doll would assume over the next six decades.

From the mundane to the highly unusual, it seemed there was nothing Barbie couldn’t do.

She was an astronaut in 1965. An Army medic in the ’90s. A dancing princess in the animated movies of the early 2000s.

At one point, she was even a cat burglar.

That borderline-comedic versatility had generations of girls in a chokehold—and over 200 careers and 60 years later, a Barbie-based movie would have the same effect.

New outfits, TikToks, chart-toppers.

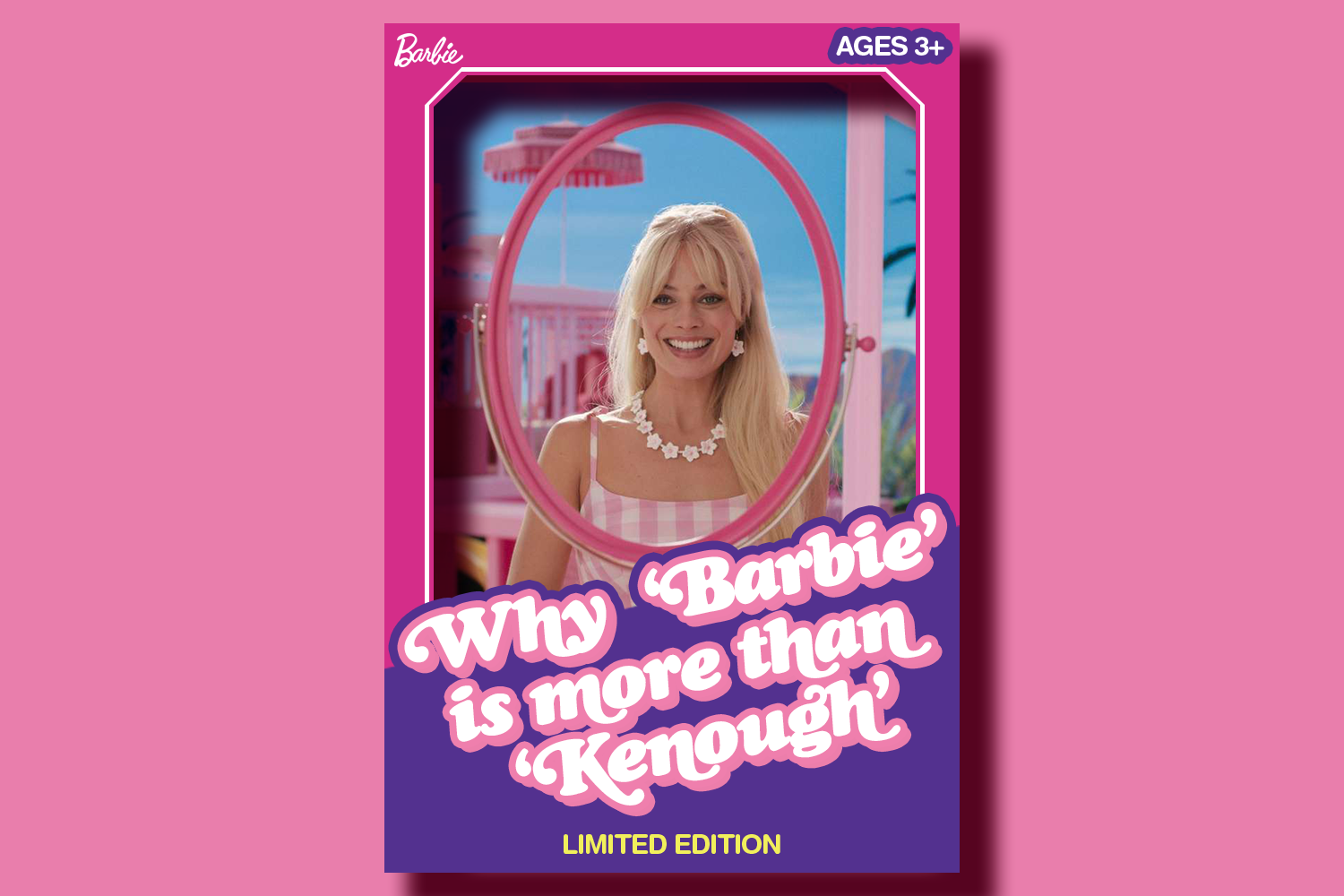

Like the titular doll, 2023’s relentlessly promoted film “Barbie”—which at first appeared merely a reason to wear pink and caption an Instagram post, “Hi, Barbie!”—delivered unforeseeable depth and versatility.

And like the doll that inspired it, the film gained its ‘chokehold’ status swiftly.

Grossing $356 million in cinema’s biggest opening weekend for a film directed by a woman, the picture hit the billion mark just 17 days after release—another first for a female director.

But the “Barbie” legacy lies not in the number of people the film’s expansive marketing budget got in the door. It’s the number left dissecting the movie’s every nuance and detail weeks after they left the theater.

From young doll fanatics to middle-aged women, angry politicians to dads just along for the ride in the Star Vette, everyone seems to be talking about why they love or hate “Barbie.”

With “Barbie” arriving on streaming services this September, here’s a look at why this Barbie sides with the lovers.

Ryan Gosling as stupidly suave Ken. Michael Cera as the wonderfully weird Alan. Will Ferrell as a perfectly punchable manifestation of capitalism. While I could praise the well-casted men of “Barbie” for their performances any day, they’re still just Kens.

Barbie, she’s everything.

They—Margot Robbie and America Ferrera—were everything.

It doesn’t get more perfectly Barbie than Robbie.

Other stars considered for the titular role, like Amy Schumer and Anne Hathaway, simply wouldn’t have brought the movie to thematic fruition.

Too many of the film’s underlying messages are contingent on the lead’s ability to be everything that makes stereotypical Barbie Barbie—the hair, the perfectly straight teeth, the effortlessness.

And no one can pull off that flawlessly blonde and beautiful persona like Robbie—cast as the trophy wife, the queen, the attractive young actress of her previous films—can.

For the movie’s messages about facing problems head-on, that look was not an accessory—but a necessity.

Robbie’s portrayal of the plastic, too-perfect original doll served as a reminder that although the appearances and occupations of Barbies have since diversified to reflect the real world, the 1959 doll is still vital—as an instrument for acknowledgment and confrontation.

We needed a stereotypical Barbie, of all Barbies, not to promote harmful beauty standards—but to be blatantly problematic enough to spark conversation and confrontation.

We needed a stereotypical Barbie to reveal that although the expositional Barbieland seemed as perfect as she was, it was too much the opposite of the real world—a toxically positive environment where relationship problems and Weird Barbie’s ostracization were never confronted.

And we needed a stereotypical Barbie to be just unrealistic enough for Ariana Greenblatt’s character Sasha to reject it—causing a rift with her mother that ultimately makes confrontation in Barbieland possible.

To have anything less than a perfect, atrociously stereotypical Barbie drive the plot would be to run counter to the movie’s message about the vitality of confronting our issues.

Without Robbie’s one-in-a-million perfection, without an actress who looks too unmistakably like the doll, the confrontation theme would be lost. Like Ken, the movie would be nothing without her.

But the movie would also be nothing without America Ferrera’s character, middle-aged mom Gloria—whose workplace misery and fear of dying initiates the entire “Barbie” plot.

To cast Ferrera, a Latina woman, in this grand but whimsical role was to defy precedent in the best possible way.

Ferrera herself has spoken on the importance of letting Latino actors join the ‘fun’ side after spending years reduced to immigration or discrimination storylines on-screen. While these stories deserve to be told, Ferrera and audiences agree: It’s nice to see more holistic representation.

“I am so grateful to Greta [Gerwig] for writing the character Latina,” Ferrera said in a Good Morning America interview. “And inviting us to be part of the fun, inviting us to be represented in this big, shiny, beautiful, hilarious world.”

It’s a good thing Ferrera did get that invitation—because by casting her, “Barbie” broke a boundary before it ever broke a billion.

Billie Eilish. Ice Spice and Nicki Minaj. Dua Lipa.

It’s nearly impossible to listen to WBNQ on the drive to school without hearing at least one hit from the Barbie movie—for good reason.

“Barbie: The Album” teems with catchy rhythms and thought-provoking lyrics that fit the movie—and its audience—like a Best Fit Barbie doll’s gloves. From upbeat tracks like Lizzo’s “Pink” to Billie Eilish’s reflective “What Was I Made For,” the film’s release gave audiences something new for every mood, every type of scene— even amid prime opportunities to utilize song covers.

Like the movie’s doll-inspired characters, the Barbie soundtrack could have relied on popular stand-bys on existing ideas.

James Brown’s “It’s a Man’s Man’s Man’s World”?

Practically written for the campfire scene that leaves the Kens, who “have nothing without [their] woman or a girl,” feeling worthless without their girlfriends’ doting love.

Dua Lipa’s “Levitating”?

Fitting for one of the movie’s early dance scenes, “where the music don’t stop for life”— literally, given the unprecedented nature of stereotypical Barbie’s death comment.

But ‘fitting’ is not kenough for Barbie.

‘Fitting’ isn’t even good enough for “Levitating” artist Dua Lipa herself.

Dua Lipa not only debuted a new dance-pop hit, “Dance the Night,” specifically for the movie, but spent hours rewriting its lyrics after she saw the song’s accompanying dance scene.

Synching the word “up” to Robbie’s hand raise. Matching the lyrics “come along for the ride” with a gesture.

For the already-catchy tune to be honed so precisely, for Dua Lipa to tailor a song to the choreography and not vice versa, is to obtain a rare level of perfection.

A level matched by starkly different but no-less-genius hit “What Was I Made For”—a welcome return to Billie Eilish’s softer “Ocean Eyes” style.

The song, featured in a mid-movie montage of real women, doesn’t just match the film perfectly; it matches the lived experiences of its predominantly young adult audience.

Its 300 million Spotify streams are 300 million times listeners felt wistful—longing for the blissful, toy-filled afternoons of their youth and for the day they find clarity and meaning in life once again.

Simultaneously mourning the loss of childhood and looking optimistically into the future, the song aptly describes its own effect on listeners: “I don’t know how to feel” is the song’s most frequent line.

But even if audiences don’t know exactly how to feel, how to label the emotion that emerges while listening to the song alongside Barbie’s long-awaited tears, the delicate rhythm and lyrics of longing make are bound to make audiences feel something—and feel it strongly.

As is the rest of the soundtrack.

Dua Lipa’s “Dance the Night” feels magical, impossible to listen to without invoking a memory of the “Barbie” party scene.

“Barbie World” with Nicki Minaj, Ice Spice and Aqua makes us feel like dancing in our seat.

Even “I’m Just Ken” makes us feel melodramatic in the best possible way.

It’s no wonder that songs from “Barbie: The Album” remain ubiquitous months after the film’s release.

Just as there’s a Barbie for every type of girl, there’s a Barbie song for every type of person, every type of situation and every feeling in the world beyond Barbieland.

Beneath the surface of the film set’s hot pink paint coatings, behind the closed doors of the Dreamhouse, “Barbie” is out to prove that movies based on toys don’t have to be immature. They can unwrap and flesh out real themes.

While some critics have called the film anti-man, “Barbie” is not about women or men at all. It’s about womanhood and manhood as concepts—and the systemic and societal institutions that put both in boxes on shelves.

From a script that teemed with statements about gender and the capitalistic society enclosing it, here are the points that made screenwriters Greta Gerwig and Noah Baumbach’s genius clearer than a plastic Barbie box.

Perhaps no part of the “Barbie” script has been more widely reposted and praised than human character Gloria’s monologue about womanhood.

The speech from the movie’s second half brilliantly describes the double standards women endure daily.

Gloria repeatedly insists that as a woman, “you have to be” one of many ‘desirable’ female characteristics—thin, wealthy, appreciative of motherhood—to be liked.

But to be too thin, prideful about money or proud of one’s kids is to suddenly become unbearable.

You must be good, but not too good. You must have this, but not too much of it.

The first half of the monologue proceeds with this impactfully simple cadence of expectations and limits, expectations and limits, perfectly emulating the “too contradictory” nature of being a woman in modern society.

When Gloria finally breaks from that cadence, her exasperation at the gratitude demanded of women is expressed so bluntly—each sentence begun so colloquially with a conjunction—it’s almost comical.

A comedy that quickly fades to incredulity when we remember its ironic accuracy.

“But always stand out and always be grateful,” she says. “But never forget that the system is rigged. So find a way to acknowledge that but also always be grateful.”

Women are actually expected to acknowledge sexism, Gloria notes, but with a shrug and a laugh. The very way women address sexism is criticized with more sexism.

Even the solution becomes a problem in this world where “nobody gives you a medal or says thank you.”

A truth so brutal that Gloria concludes her remarks not with a gallant call-to-action, but with an admission of exhaustion and a ‘beats me’:

“I’m just so tired of watching every single other woman tie herself into knots so that people will like us. And if all of that is also true for a doll just representing women, then I don’t even know.”

Chase that “I don’t even know” with Billie Eilish’s lyric, “I don’t know how to feel,” later in the movie, and you get the ultimate screenwriter-meets-lyricist moment—and a reason to cry.

In sadness for the injustice the writing conveys, but also in admiration for the beautiful, full-circle way it is assembled.

“Barbie” is an almost complete reversal of the archaic plot that pervades American cinema.

Woman lacks an identity outside of her man. Woman finally discovers her true self without her man. Woman ends up with a man anyway.

It’s an endless cycle that “Barbie,” in making Ken the dependent, outwardly one-dimensional suitor, manages to detach from an existing body of cinematic works enough to flip on its head.

Now, it’s the man struggling to find meaning without his partner—a premise that sent shockwaves of protest through audiences who have happily watched women in an identical position for decades.

But contrary to critics’ claims, the reversal isn’t just a display of irony designed to ‘show men how the women feel.’

Because Ken’s one-dimensionality in the movie—his being “just Ken”—only lasts so long.

His journey to the real world teaches him that although the patriarchy and masculine ideals seem to be just that—ideal—while they are only about power and bravado, living up to the ‘masculine’ hype really hurts.

Men. Not just women—society’s view of what it means to be masculine hurts men, too.

As soon as Ken’s mask of real-world-inspired power slips, it’s “I only exist within the warmth of your gaze” and “I’m just another blond guy who can’t do flips”—sad realities that reflect how little men are allowed to be beyond the emotionless wielder of power.

Realities lamented in “I’m Just Ken,” an angsty ballad that sets up Barbie’s long-overdue task for her friend: finding himself outside of the “Barbie and Ken” dynamic.

But when Barbie says, “You have to figure out who you are without me,” she doesn’t just mean Ken needs an identity separate from his long-distance low-commitment casual girlfriend.

Barbie means that Ken needs to question who he is when he’s not playing into the entire macho girlfriend-courting, Mojo-Dojo-Casa-House-owning, mink-fur-wearing image that society has thrust upon him.

She means the common man is disadvantaged for having his worth chalked up to who his girlfriend is, the home he can afford, the clothes he can wear on his back—all while allowing his true feelings to pile up so high they require a dance number to finally release.

So when Ken realizes he has an identity independent of his less-than-desirable personas earlier in the film—Barbie’s boyfriend with too little power and the manly man with too much of it—he is so relieved he shouts, “Ken is me!”

Seven times, in fact—more than any other line in the movie.

If this emphasized realization that Ken is “Kenough” with his emotions and without his status, the scene’s somber blue lighting that extends sympathy for Ken’s existential grief, and the assertion that “no Barbie or Ken should be living in the shadows” don’t cleverly advocate for men in a toxically masculine world… then pink isn’t Barbie’s signature color.

And pink is undoubtedly Barbie’s signature color.

When “Barbie” rose to ubiquity this summer, the doll wasn’t lonely at the top of the box office shelf.

“Barbenheimer,” the portmanteau for the simultaneous “Barbie” and “Oppenheimer” releases, marked the United States’ first top-five opening weekend in history to split sales so evenly between two pictures.

Temperatures soaring to record highs and wildfires raging this July, moviegoers used the double picture to escape into air-conditioned theaters—only to witness on-screen destruction as dire as the crises outside.

And as human lives crumbled amid a human-spurred climate crisis, “Barbie” and “Oppenheimer”—two films about humankind destroying humankind—unironically flourished.

One film about humans ravaging other human lives with an atomic bomb. The other about human-imposed ideals and systems ruining the human experience.

Billions of ticket dollars later, consumers had reengaged with the all-but-abandoned double feature concept in the name of one theme: self-destruction.

So as fall begins and we drift away from the destruction-heavy summer film hype, we relish the cooler weather and watch as the nation goes up in flames in a less literal sense for now.

If nothing else, at least we can rewatch and appreciate the Barbie movie as the world burns.

IF YOU SHARE THE INKSPOT'S PASSION for empowering Normal Community's aspiring journalists and equipping them with viable and valuable digital media skills, please consider contributing to our cause.

Your support plays a vital role in enabling the Inkspot to invest in top-tier equipment, maintain memberships in distinguished professional organizations such as the Journalism Education Association and National Scholastic Press Association, send our students to compete at state and national contests, and attend the National High School Journalism Convention.

Your generosity is the key to providing these students with a truly enriching educational experience. THANK YOU.

![Coach Drengwitz on the loss to Mt. Carmel, 2024 season [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Postseason-presser-feature-1200x800.png)

![IHSA 7A Football Playoffs Quarterfinals: Ironmen head coach on facing the Mt. Carmel Caravan [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/0w12-web-feature-1200x800.png)

![Halloween candy cross section quiz [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Candy-cover-big-900x675.png)

![Average Jonah? [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/average-jonah-900x600.png)

![Cell phone ban in schools? Community responds to proposed legislation [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Sequence.00_01_09_19.Still001-1200x675.png)

![Ironmen spring sports update: April 9 [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/sports-recap-square-1200x1200.png)

![Ironmen in the hunt: Coach Feeney talks Big 12 Title race ahead of PND matchup [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/feeney-1200x675.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Halloween [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/tot-Halloween-YT-1200x675.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Fall favorites [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/ots-fall-web-1200x800.png)

![On the Spot – Teachers tested on 2023’s hottest words [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/On-the-Spot-Teachers-tested-1200x675.png)