For Dr. Valentine Walker life has been a journey.

The journey started when he “met a beautiful peace corp volunteer” and moved from his homeland in Jamaica to the United States where he became a dual credit Environmental Earth teacher at NCHS and NCWHS.

Walker grew up along the countryside in a small town in the St. Elizabeth province in Jamaica. There Walker learned the importance of education and the direct correlation hard work has to success.

Walker’s small hometown shared many of the same values that small towns in America also have.

“We as a community, we loved each other,” said Walker.

Being born to parents who were school principals, Walker’s family in Jamaica had a certain prominence. They were given a high status based on their comfortable economic means. They were relied on. They were looked up upon.

“If there was an emergency in the middle of the night,” said Walker, “we were the ones that had a car in the community, so I got my fair share of rushing moms in labor to the hospital 11 miles away.”

Walker still misses Jamaica and still visits frequently, but as for America, “this is my home,” he said.

The journey between two different countries isn’t always easy.

First of all, there is the climate.

“I just can’t get used to the cold,” Walker said.

But then also, when you move from one country to the next there are complications: credits don’t necessarily transfer. “You gotta figure all of that out,” said Walker.

While Walker was figuring all that out, he worked as the Director of Teen Programs for the YMCA in Miami, Florida.

Walker worked with the kids who had a difficult past. Walker worked to try and make sure those kids didn’t have a just as difficult future.

Another complication that can happen when making the move between two different countries is the language.

In the first couple years Walker had lived in the States, “I had a much thicker accent,” he said.

Words like batteries are pronounced differently in Jamaica than they are here and that created some issues.

“Students were basically humiliating me for mispronouncing the word,” said Walker.

Walker had to relearn the pronunciation of different words.

But pronunciations weren’t the only thing Walker had to relearn.

When you move from a hot climate culture like Jamaica to a cold climate culture like the States, the level of interaction between neighbors is a big adjustment.

“I can just remember,” said Walker, “getting frustrated with the limited interaction you have with your neighbors.”

In Jamaica, the tone is completely different.

“Jamaicans are very social people,” said Walker.

On an average day, people will just sit, relax, and socialize.

“Jamaica is a very laid back place.”

Kids spend their time playing soccer and going to the beach.

“It’s lots of interactions with people,” Walker said.

“When I grew up we didn’t have cell phones or phones period. For most of my childhood, we didn’t have electricity so entertainment came through interacting with people.”

Even though the culture change can be hard, there was a part of Jamaican culture that Walker was able to carry with him to the States.

Soccer is embedded in the Jamaican culture.

The rivalries. The competitiveness. The creativity of the game. For Walker, all appeals of soccer.

“I don’t even know how to describe it,” Walker said. “You just see it in you, you have a dying love for it.”

When Walker moved to the States he brought that aspect of Jamaica’s culture with him by coaching the boys and girls soccer team at NCWHS.

“I’m passionate about the game, so I spend a lot of time coaching,” said Walker.

Walker’s passion for coaching on and off the field lead him to journey back to Jamaica, this time with players from his soccer team.

1,722 miles overseas, Walker’s players hosted soccer clinics, did community service projects, and interacted with the local high schoolers.

“[Jamaica] is a third world country, so it comes with its fair share of violence and exposure to drugs,” said Walker.

It can be very “nerve-racking” taking high schoolers to Jamaica, said Walker.

“There are a lot of uncertainties when you go into a third world country, there’s the high crime rate, there’s the traffic.”

But despite it all, Walker still believes “the benefits of a trip like that outway the risks.”

“When you take students back to Jamaica, and show them what 3rd world country kids have to go through to get an education, it really makes them more appreciative of what they have here.”

When Walker started teaching in the States he began to notice that “not everyone gets the message that education is the means for success.”

Walker, having seen schools from both sides of the world, recognizes how extremely blessed students at NCHS and NCWHS are- how many possibilities are open to them.

Buses. Smart Boards. Lunches. Computers. Students in Jamaica don’t have those types of resources.

“You have all the resources,” said Walker, “go out and find those resources, make use of them, work as hard as you can, and you can achieve anything, especially in education.”

“Put the time in and you will be successful.”

When Walker made the journey from Jamaica to the States his plan wasn’t always to be a teacher.

“I went into teaching as a stepping stone, perhaps, to do it for a couple of years, and then do something else.”

Walker always had the goal to work in a private sector or be a scientist in a lab just “tinkering with stuff.” But as the journey went on, the winds shifted.

“Because at some point,” said Walker, “you start to prioritizes things a little bit differently.”

Other jobs would have meant being away from family or taking a pay cut.

“Teaching affords me a stable income and time enough to be with my family and do things as a dad that I value like coaching my kids.”

A journey. A drive. A sacrifice. That’s how Walker got to where he is today. Journeys don’t always take its travelers where they plan to go, but then again if it did, would it really be a journey?

![Community honors longtime coach Mr. Bryan Thomas before Oct. 3 game [photo gallery]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Thomas-6-1200x1200.jpg)

![Postgame: Drengwitz on Community’s 56-6 win over Champaign Centennial; staying unbeaten in Big 12 [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/10.17_FBwChampCent56-6_POST_thumb.png)

![Halloween candy cross section quiz [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Candy-cover-big-900x675.png)

![Average Jonah? [quiz]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/average-jonah-900x600.png)

![[Photo Illustration]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/trigger-words-1.png)

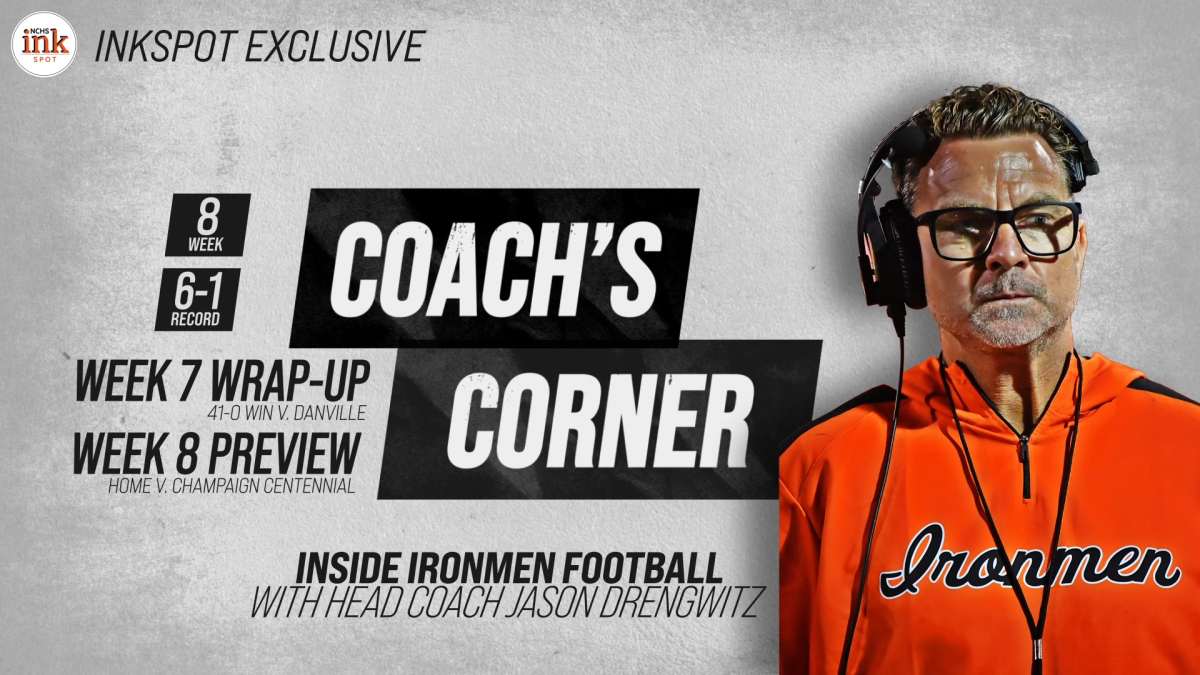

![Week 7: Coach Drengwitz recaps the Ironmen’s win over Bloomington, talks Danville [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Vikings-feature-Image-1200x675.png)

![Week 5: Coach Drengwitz previews the Ironmen’s matchup vs. Peoria Manual, recaps Week 4 [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Week-5-v-Rams-1200x675.png)

![Postgame reaction: Coach Drengwitz on Community’s 28-17 Loss to Kankakee [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Week-4-postgame--1200x675.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Halloween [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/tot-Halloween-YT-1200x675.png)

![On the Spot: This or That – Fall favorites [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/ots-fall-web-1200x800.png)

![On the Spot – Teachers tested on 2023’s hottest words [video]](https://nchsinkspot.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/On-the-Spot-Teachers-tested-1200x675.png)